Quasars, The Bright Hearts of Distant Galaxies

Introduction

Quasars are some of the most extreme, confusing, and beautiful objects the universe has ever produced. They look like tiny star like points in many telescopes, yet they can outshine entire galaxies. They are seen from very far away, meaning we often observe them as they were when the universe was young. By studying quasars, astronomers have learned about supermassive black holes, how galaxies grow, what the early universe was like, and even what fills the space between galaxies. If you want one topic that connects black holes, cosmic evolution, and the largest scales in the cosmos, quasars are it…

At first glance, a quasar can seem like “just a bright dot.” But that dot is the result of gravity doing something both brutal and efficient. A supermassive black hole, sitting in the core of a galaxy, gets fed by gas and dust. The material does not fall straight in. It spirals, heats up, and turns into a blazing engine that can be seen across the observable universe.. When astronomers say quasars are among the brightest objects known, they mean it in a literal way, you can detect them from billions of light years away, even with surveys that cover huge areas of the sky.

This article goes step by step through what quasars are, how they were discovered, what their parts are, how we detect them, and why they matter so much. The goal is not just to memorize a definition, but to understand the full story..

What exactly is a quasar?

The word “quasar” comes from “quasi stellar radio source.” In the 1950s and early 1960s, astronomers found extremely bright radio sources in the sky that looked like normal stars in optical images. That was the strange part. Stars are inside our galaxy, but these objects behaved differently. When astronomers finally measured their spectra, they discovered huge redshifts, meaning these sources were incredibly far away. If something that far away still looks so bright, it must be producing a ridiculous amount of energy.

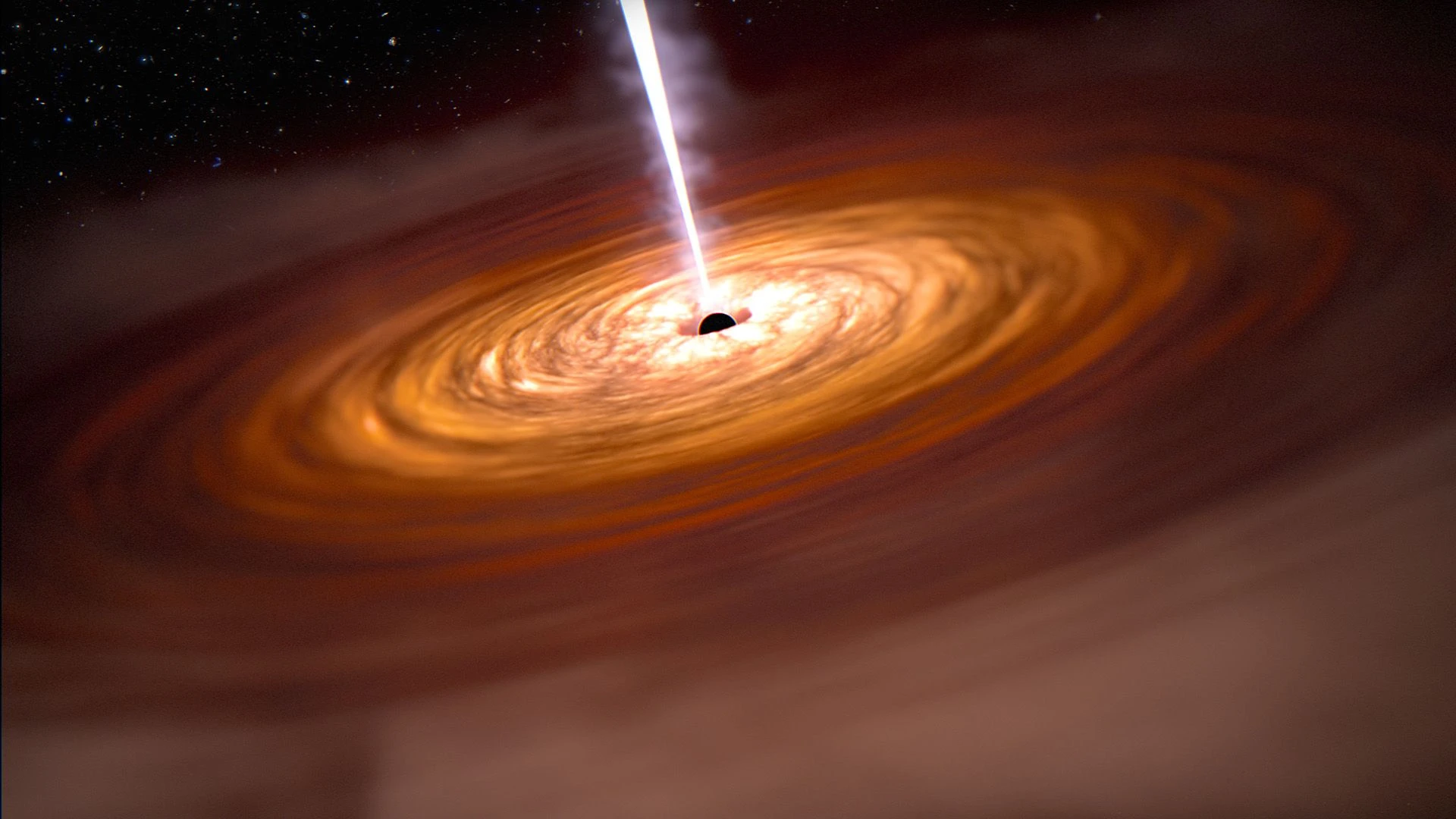

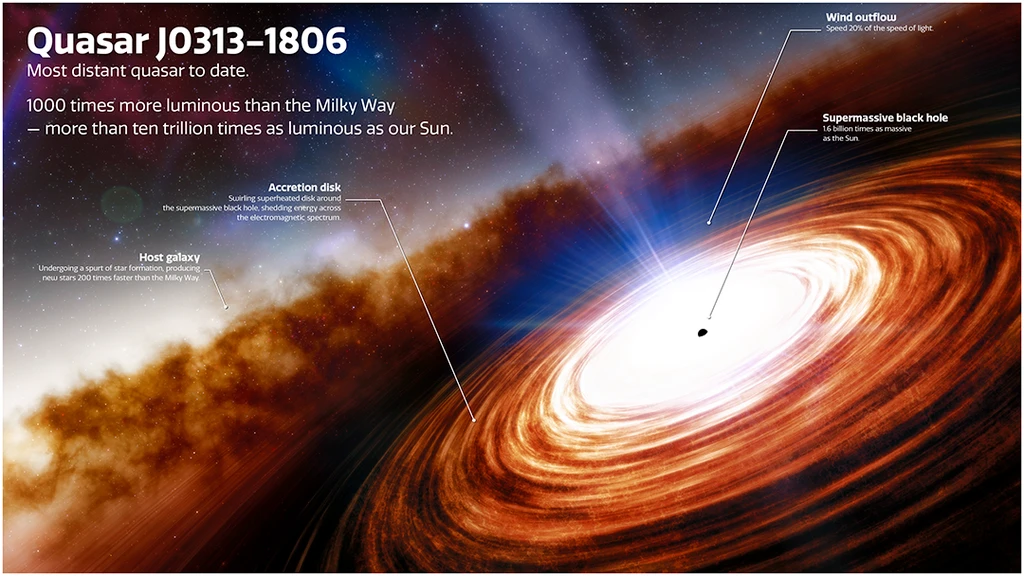

A quasar is now understood as the brilliant central region of a galaxy that is powered by matter falling into a supermassive black hole. The black hole itself does not glow, but the material around it can. When gas and dust spiral toward the black hole, they form a hot, spinning structure called an accretion disk. Friction, compression, and magnetic forces heat the disk to very high temperatures. This hot disk radiates across many wavelengths, from infrared and visible light to ultraviolet and X rays. In some quasars, powerful jets shoot out at near light speed, producing strong radio emission and intense high energy radiation.

So, a quasar is not a separate “type of star.” It is the active heart of a galaxy, and its engine is a supermassive black hole being fed by surrounding matter.

It can help to remember this, “quasar” is a label for an active phase. The same galaxy could be quasar bright during one era, then quiet later. In other words, quasars are not a permanent class of galaxy, they are a stage in a galaxy’s life..

The quasar engine, how can a black hole power light?

It sounds like a paradox. Black holes pull everything in, so how can they be among the brightest things in the universe? The key is that the light does not come from inside the event horizon. It comes from outside, in the swirling, heating material before it falls in.

When matter falls into a black hole, gravitational energy is converted into heat and radiation. This is one of the most efficient known ways to produce energy. For comparison, nuclear fusion in stars converts a small fraction of mass into energy. Accretion onto a black hole can convert a much larger fraction of the infalling mass into radiation. That means you do not need a huge amount of matter compared to the energy output. Just a steady flow of gas can make a quasar blaze brighter than a galaxy filled with billions of stars.

The accretion disk is not calm. It is turbulent, magnetized, and constantly shifting. Some regions heat more than others. The disk can also have a “corona,” a region of extremely hot particles above the disk that produces X rays. Surrounding the disk, there may be thick clouds of gas moving fast, producing broad emission lines in the spectrum. Farther out, cooler gas produces narrower lines. These features help astronomers map the structure of a quasar even though it is too tiny to resolve directly in most cases.

One more important idea is “efficiency.” If you drop material into a deep gravitational well, you can release an enormous amount of energy before the material is lost to the black hole. This is why quasars can rival, or exceed, the combined light of an entire galaxy.. It is gravity as a power station, not fire, not fusion, but gravity.

Learn more: Want the basics of black holes, event horizons, and how they form? Learn more about Black Holes

Supermassive black holes, the heart of the story

Quasars require supermassive black holes, meaning black holes with millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun. Almost every large galaxy seems to contain one of these in its center. Our Milky Way has one too, called Sagittarius A*, but it is currently quiet. It is not acting like a quasar because it is not being fed at a high rate right now.

One of the big questions in modern astronomy is how supermassive black holes formed so early. Some of the most distant quasars we see already have black holes with billions of solar masses, even when the universe was less than a billion years old. That creates a growth problem. How did they get so massive so fast? There are several ideas, like direct collapse of massive gas clouds, rapid growth through dense feeding, or merging of early black hole seeds. This is active research, and every new high redshift quasar helps test these ideas…

That early growth mystery is one reason quasars are treated like “cosmic fossils.” Each far quasar is a data point from a time when galaxies were still assembling. The more distant the quasar, the more it pushes our models to explain how black holes and galaxies built themselves so quickly..

A quick history, how we figured them out

Quasars were a major shock to astronomy. Early radio surveys found bright sources with no obvious counterparts. When optical counterparts were identified, they looked like faint stars. The breakthrough came when astronomers recognized that the strange spectral lines were normal lines shifted by enormous redshifts. That meant these objects were at cosmological distances, not inside the Milky Way.

Once that distance was accepted, the energy output was almost unbelievable. At first, people proposed many exotic explanations. Over time, the black hole accretion model became the best fit, because it could explain the luminosity, the variability, the emission lines, and the multi wavelength behavior.

Today, quasars are considered a phase in a galaxy’s life. A galaxy may light up as a quasar when a lot of gas is driven toward its center, often during galaxy interactions or mergers. Later, the black hole runs out of easy fuel, the quasar fades, and the galaxy becomes more normal looking.

Modern surveys have expanded the quasar story even more. We now know there are many “hidden” quasars covered by dust, and there are also weaker active nuclei that are like smaller cousins of quasars. So the quasar idea grew into a bigger picture, galaxies and their central black holes evolve together, switching between quiet and active periods..

What do quasars look like, and how do we detect them?

Even though they can be immensely luminous, quasars are usually so far away that they appear as a point source in many images. But they have unique signatures.

Their spectrum

A quasar spectrum often shows strong emission lines. These lines come from different atoms and ions in hot gas, like hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, magnesium, and others. The lines can be broad, meaning the gas is moving extremely fast, sometimes thousands of kilometers per second. The exact pattern of lines, and how wide they are, gives clues about the temperature, density, and motion of the gas.

Their redshift

Redshift is a measure of how much the universe expanded since the light left the quasar. High redshift quasars are among the most distant objects known. Because of redshift, light that started as ultraviolet may arrive as visible or infrared. This is why infrared telescopes are so important for finding the earliest quasars.

Their variability

Quasars can change brightness over days, months, or years. This variability is a clue that the emitting region is relatively compact. A galaxy of stars usually does not vary quickly as a whole, but a small region near a black hole can. Variability studies also help map the size of the emission line regions using a technique called reverberation mapping, where changes in the disk light cause later changes in the lines.

Multi wavelength emission

Quasars shine across the electromagnetic spectrum. Some are especially bright in radio, often due to jets. Many are bright in ultraviolet and X rays, due to hot inner disk regions and the corona. Others are heavily obscured by dust and are easier to detect in infrared. Observing quasars in multiple wavelengths gives a fuller picture of what is happening.

In practice, astronomers usually combine several clues. A candidate might be selected based on color in sky survey images, then confirmed with spectroscopy. Or it might be found in X rays, then matched to an optical source. It is like detective work across wavelengths..

The accretion disk, corona, and the surrounding regions

To understand quasars well, it helps to imagine layers.

- Inner accretion disk

This is the hottest region, close to the black hole. It emits strongly in ultraviolet and visible light. Its exact temperature depends on black hole mass and how fast matter is falling in. - Corona

A hot region above the disk that can produce X rays by scattering lower energy photons up to higher energies. The corona’s physics is still not fully nailed down, but magnetic activity likely plays a major role. - Broad line region

Clouds of gas orbiting close in, moving fast, producing broadened emission lines. These clouds are not fully understood, but their behavior is crucial for measuring black hole masses. - Dusty torus

In many models, a thicker ring or torus of dust surrounds the inner region. This dust can obscure the quasar from some viewing angles. The dust absorbs ultraviolet and visible light and re emits it in infrared. - Narrow line region

Gas farther out moves more slowly and produces narrower lines. - Host galaxy

The galaxy around the quasar, sometimes hard to see because the central quasar is so bright. With powerful telescopes and clever processing, astronomers can separate the quasar light and study the host galaxy’s stars and structure.

These “regions” are not just names. They reflect what we can infer from light. Broad lines, narrow lines, infrared bumps, X ray slopes, all of these act like fingerprints that tell us which parts are present and how active they are..

Quasar types, why do some look different?

Quasars come in several varieties. Some differences are intrinsic, and some may depend on viewing angle.

Radio loud vs radio quiet

Some quasars produce strong radio emission, often linked to jets. These are called radio loud quasars. Others have weak radio emission and are radio quiet. The reason for this difference could involve black hole spin, magnetic field configuration, and how the galaxy feeds the black hole. Jets are complex, and not every active black hole makes powerful ones.

Obscured vs unobscured

If a quasar is surrounded by dust and gas that blocks our direct view of the bright disk, we may see a different spectrum. In some cases, the broad lines are hidden and only narrow lines are visible. These are sometimes called Type 2 quasars, while those with broad lines visible are Type 1. Unification models propose that many of these differences are mainly viewing angle, like whether the dusty torus blocks the inner region from our line of sight. But there are also real differences in how much gas and dust is present, so it is not only angle.

Blazars

If a jet is pointed almost directly at Earth, the object can appear extremely variable and bright due to relativistic beaming. These are called blazars, and they are often strong in gamma rays. They are related to quasars but have special observational features because of the jet orientation.

When you read about different “types,” remember that nature does not always place objects into neat boxes. Some quasars fall between categories. Some change over time. Astronomy is full of messy in between cases..

Measuring black hole mass with quasars

A key reason quasars are useful is that they let us estimate the mass of their central black holes. One common method uses emission line widths and the size of the broad line region. If gas is orbiting under gravity, faster motion implies a stronger gravitational pull, which implies a more massive black hole. Reverberation mapping can estimate the size of the broad line region by measuring time delays between changes in the continuum light and the response of emission lines. Combine region size with velocity, and you can estimate mass.

For very distant quasars, direct reverberation mapping is harder because it requires long monitoring, but astronomers use empirical relationships based on line widths and luminosity to estimate mass. These methods have uncertainties, but they have revealed a wide range of supermassive black hole masses, including the monstrous billion solar mass black holes in the early universe.

It is also important to understand what “uncertainty” means here. A mass estimate might be off by a factor of a few, sometimes more, depending on the method and line used. But even with that uncertainty, the conclusion remains clear, some early quasars host truly gigantic black holes.. That is why the growth problem is so serious.

Quasars as cosmic lighthouses, probing the space between galaxies

One of the coolest uses of quasars is not even about the quasar itself, but about what lies between us and it.

As quasar light travels to Earth, it passes through clouds of gas in intergalactic space and within galaxies along the line of sight. Those gas clouds absorb specific wavelengths, leaving absorption lines in the quasar spectrum. By analyzing these absorption lines, astronomers can study the composition, temperature, motion, and density of the gas in places we cannot see directly.

The Lyman alpha forest

For high redshift quasars, there is a dense pattern of absorption lines in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum, shifted into visible or infrared. This is called the Lyman alpha forest, caused by many clouds of hydrogen gas at different redshifts. It is like a barcode of the universe’s structure. Studying it tells us about the distribution of matter on large scales, the ionization state of the intergalactic medium, and how it changed over time.

Damped Lyman alpha systems

Some absorption features are very strong, indicating large amounts of neutral hydrogen. These damped systems can be linked to galaxies or proto galaxies and are important for understanding how gas turned into stars over cosmic time.

Metal absorption lines

Heavier elements, called “metals” in astronomy, also leave absorption lines. These show that even early in the universe, some regions were already enriched by previous generations of stars. This helps trace the history of star formation and galaxy evolution.

Quasars are basically backlights for the universe. If you shine a flashlight through fog, you can learn about the fog by how it dims and changes the beam. Quasars do that on cosmic scales, except the “fog” is gas spread across millions of light years..

Quasars and the early universe, the era of reionization

After the Big Bang, the universe cooled enough for electrons and protons to combine into neutral hydrogen. This neutral gas filled space, making the universe “dark” in some wavelengths. Later, the first stars and galaxies formed and produced intense ultraviolet light that reionized the hydrogen, turning much of it back into plasma. This period is called the epoch of reionization.

Very distant quasars, with redshifts above about 6, are seen near or within this era. Their spectra can show how much neutral hydrogen existed at that time. If the intergalactic medium is more neutral, it absorbs more light in specific ways, producing features like the Gunn Peterson trough. By studying these early quasars, astronomers can map when and how reionization happened. It is like using a lighthouse to see fog that no longer exists today…

Learn more: To understand why reionization matters, it helps to know the full early timeline. Learn more about the Big Bang Theory

How quasars affect their galaxies, feedback and cosmic regulation

Quasars are not just passive beacons. They can strongly influence their surroundings. The energy output from a quasar can heat gas, push it outward, and change how a galaxy forms stars. This is called quasar feedback.

If a quasar blows out or heats the gas in a galaxy, that gas cannot cool and collapse into new stars as easily. This could help explain why some massive galaxies stop forming stars and become “red and dead,” filled with older stars. Feedback is also used in galaxy evolution models to reproduce the observed relationship between black hole mass and galaxy bulge properties, like the M sigma relation, which suggests black hole growth and galaxy growth are linked.

Feedback can happen through radiation pressure, winds from the accretion disk, and jets. Jets can inject energy far out into the galaxy and even into galaxy clusters, affecting hot gas over huge distances.

But feedback is complicated. In some cases, quasar activity might compress gas in certain regions, triggering star formation rather than stopping it. The full story depends on geometry, the amount of gas, and the environment.

Think of it like this, a quasar is not only a consumer, it is also a furnace and a blower. It can “cook” the surrounding gas, and it can “push” it. That is why it can regulate the galaxy that feeds it.. This connection is one of the biggest themes in modern galaxy evolution.

The quasar life cycle, are quasars permanent?

A quasar is generally a phase, not a permanent state. The black hole needs fuel. When a lot of gas falls in, the galaxy’s center becomes active. Over time, the fuel supply changes. The quasar may dim or switch off. It might turn on again later if new gas flows into the center. So galaxies can have multiple active episodes over their lifetimes.

The brightest quasar phase might be relatively short, maybe tens of millions of years, which sounds long to humans, but short compared to the age of galaxies. There are also lower level active galactic nuclei, like Seyfert galaxies, which are less luminous than quasars but powered by the same basic mechanism.

Understanding quasar lifetimes helps answer how black holes grew. If quasars shine near their maximum possible rate for long enough, they can gain huge mass. The maximum steady rate is related to something called the Eddington limit, where outward radiation pressure balances inward gravity for ionized gas. Many quasars operate near this limit.

Some galaxies might have “flickering” activity, on for a while, off for a while, depending on how gas flows in. This makes the life cycle even more interesing, because a quasar could be bright during one epoch, then nearly invisible later, then bright again if conditions change..

Quasars and jets, cosmic particle accelerators

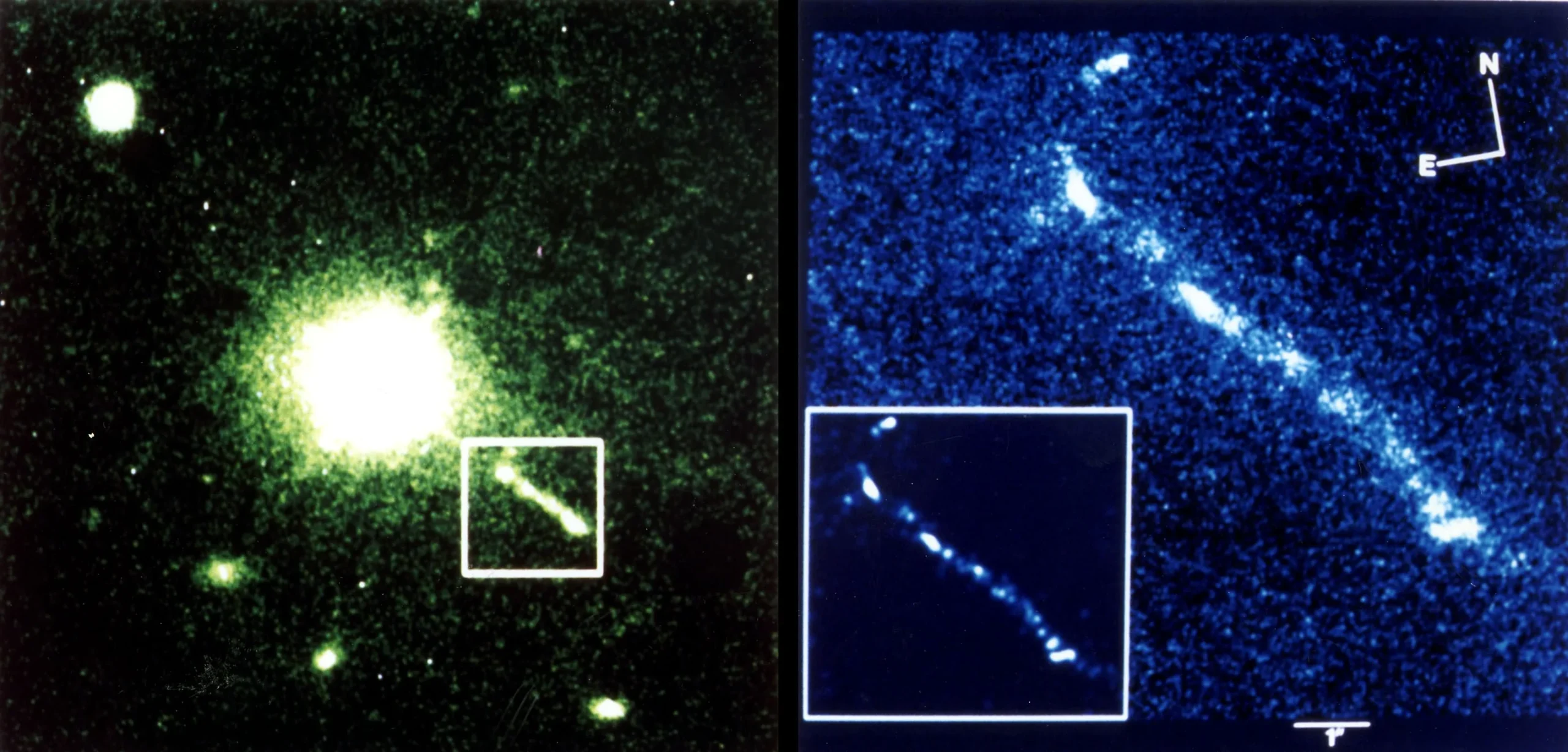

Some quasars launch jets that extend far beyond their galaxies. These jets are narrow beams of plasma moving near the speed of light. They can produce bright radio lobes where they slam into surrounding gas. They also produce synchrotron radiation, caused by charged particles spiraling in magnetic fields.

Jets matter for several reasons:

- They show that black hole systems can convert accretion energy into organized, directional outflows.

- They transport energy over enormous distances.

- They can accelerate particles to very high energies, contributing to cosmic rays and high energy emissions.

- They influence galaxy environments and clusters by heating gas and preventing it from cooling too fast.

Jets are still not fully understood in detail. Magnetic fields likely play a major role, and black hole spin might help power them through processes that tap rotational energy. But the exact balance of mechanisms is still studied.

In some cases, jets also help astronomers find quasars. A radio bright jet can stand out strongly in radio surveys, even if the optical light is partly obscured by dust..

Famous quasars and what they taught us

Astronomers often talk about quasars in catalogs rather than by catchy names, but a few became well known because they were early discoveries or have special properties.

- Some of the first identified quasars were strong radio sources, and their spectra shocked astronomers with high redshifts.

- Gravitationally lensed quasars, where a foreground galaxy bends and splits the quasar’s light, have been extremely important. Lensing can create multiple images of the same quasar and magnify it. By measuring time delays between brightness variations in the images, astronomers can probe cosmological parameters and the mass distribution of the lensing galaxy.

- Extremely distant quasars have revealed the presence of massive black holes in the early universe and helped probe reionization.

Even if you never memorize specific object names, it is worth remembering the concept, quasars have repeatedly been used as tools to study the universe, not just as objects to classify.

How do we find quasars today?

Modern surveys find quasars in huge numbers. They use multiple techniques:

- Color selection: Quasars have distinctive colors in different filters due to their spectra and redshift. High redshift quasars can “drop out” in certain bands because hydrogen absorption removes light below a wavelength threshold.

- Spectroscopic confirmation: Candidate quasars are observed with spectrographs to measure redshift and identify emission lines.

- X ray and radio selection: Some quasars are easier to find in X rays or radio.

- Variability selection: Quasars vary in brightness, and time domain surveys can pick them out from stars.

Large sky surveys have created catalogs with hundreds of thousands and even millions of quasars. This allows statistical studies, like how quasar populations change over time, how their brightness distribution evolves, and how they trace large scale structure.

There is also something important here, “selection effects.” Different methods find different subsets of quasars. Color selection might miss dusty quasars, while infrared selection might catch them. That is why astronomers combine surveys across wavelengths, to build a more complete census..

Common misconceptions about quasars

Because quasars are so extreme, misconceptions are common.

- A quasar is not a star. It only looks star like in images because it is far away and compact in appearance.

- The black hole itself is not shining. The light comes from matter outside the event horizon.

- Quasars are not all the same. There is a wide range of luminosity, radio emission, obscuration, and jet orientation.

- Quasars do not break physics. Their brightness can be explained by accretion efficiency. They are extreme but not magical.

A related misconception is that a quasar is “one object” separate from its galaxy. In reality, the quasar is the bright nucleus of a galaxy. The host galaxy is still there, it is just harder to see because the nucleus can drown it out in brightness..

Why quasars matter, the bigger picture

If you step back, quasars sit at the intersection of many core questions in astronomy:

- How did the first massive structures form?

- How did supermassive black holes grow so quickly?

- How do black holes and galaxies co evolve?

- What is the distribution of gas in the intergalactic medium?

- When did reionization occur, and how did the early universe change from neutral to ionized?

- How does energy flow through galaxies and clusters?

Quasars help answer these questions because they are bright enough to be seen across most of the observable universe. They are both signposts and engines. They show us the deep past, and they also reshape their local environments.

In a sense, quasars are among the best “multi purpose” objects in astronomy. They are laboratories for strong gravity, plasma, and magnetic fields, and they are also tools for mapping the universe on the largest scales..

A simple mental image to remember

If you want a clear mental picture, imagine a galaxy with a central supermassive black hole. Gas falls inward, forms a spinning disk, heats up intensely, and glows. The glow lights up surrounding gas clouds that produce emission lines. Dust farther out can obscure parts of this region. In some cases, twin jets blast outward along the black hole’s spin axis. From billions of light years away, that entire central drama is compressed into a tiny point of light. Yet within that point is a whole system of physics, gravity, plasma, magnetism, and cosmic evolution.

If you keep that image in your head, a lot of quasar details make more sense. Broad lines, fast gas. Infrared, heated dust. Radio, jets. X rays, corona. It all fits into one picture..

What we still do not know, and why it is exciting

Even with decades of research, quasars still have big mysteries.

- Early black hole seeds: Did the first black holes come from the first stars, or from direct collapse of huge gas clouds? Or both?

- Accretion physics: How exactly does turbulence transport angular momentum, allowing gas to fall inward? Magnetic effects like the magnetorotational instability are key, but real disks are messy.

- Corona formation: What creates the hot corona that produces X rays, and why does it change?

- Jet launching: Under what conditions do jets form, and what determines their power?

- Feedback details: When does quasar activity shut down star formation, and when might it trigger it?

- Obscured populations: How many quasars are hidden behind dust, especially in early stages of galaxy mergers? We might still be missing a significant fraction.

These open questions are not failures, they are signs that quasars are rich laboratories for understanding the universe.

Final thoughts

Quasars are among the most powerful lights in the cosmos, powered by gravity itself. They reveal supermassive black holes in action and show us galaxies in an intense phase of growth. They let us study the early universe, the matter between galaxies, and the processes that shaped cosmic history. When you look at a quasar, you are not just seeing a bright dot. You are seeing a signal from a time when the universe was younger, rougher, and still building the structures we see today…

And thats the magic of quasars, they are both a mystery and a tool. The more we study them, the more they teach us about everything else..

Learn More

Common Questions

No. They only look star like because they are far away and compact in images. A quasar is the active, extremely bright center of a galaxy, powered by matter falling into a supermassive black hole..

Because accretion onto a black hole is very efficient at turning gravitational energy into radiation. A relatively small region near the black hole can outshine billions of stars combined.

By measuring redshift in their spectra. Spectral lines shift toward red wavelengths due to cosmic expansion, and the amount of shift reveals distance and lookback time..

No. Some are radio loud with powerful jets, while others are radio quiet with weak or no jets. Jet formation likely depends on magnetic fields, black hole spin, and feeding conditions.

Because their light passes through intergalactic gas and galaxies along the way. That gas leaves absorption lines in the quasar spectrum, letting astronomers measure composition, density, and ionization even when the gas itself is invisible..

They exist today, but they were much more common in the early universe. Many modern galaxies have central black holes that are currently quiet because they are not being fed strongly.