Soyuz 11 Disaster, The Quiet Emergency That Changed Spaceflight Forever

Introduction

Some space tragedies are loud, visible, and instantly understood by the public. Others are the opposite, silent, hidden behind metal walls, and only revealed after the mission seems to have ended successfully. The Soyuz 11 disaster belongs to that second kind. The spacecraft came back to Earth, it landed on schedule, and to anyone watching from far away, it looked like a normal return. But inside the capsule, something had gone terribly wrong..

This event is one of the most important case studies in human spaceflight safety, because it was not caused by fire, explosion, or a dramatic failure at launch. It came from a chain of design compromises, timing, tiny mechanical decisions, and a very unforgiving environment. The crew of Soyuz 11 became the only humans in history to die due to exposure to the vacuum of space. Understanding what happened is not just remembering a sad story, it is learning how space agencies build safer systems, why pressure suits matter, and how one small valve can reshape an entire spacecraft program…

The Space Race Background and Why Soyuz 11 Mattered

To really understand Soyuz 11, you have to place it in its time. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Soviet Union and the United States were in a competition that was both technological and political. The Moon landings were grabbing headlines, but there was another goal running in parallel, living in space for long periods, learning how the human body reacts, and proving that a nation could operate beyond Earth not just for hours, but for weeks.

The Soviet Union focused heavily on space stations during this period. While the United States was preparing Skylab and building experience through Gemini and Apollo, the Soviets pushed toward a new type of achievement, a permanent outpost. Their first true space station was Salyut 1, launched in April 1971. This was a big step. A space station is not just a capsule you ride in, it is a place you live in, work in, maintain, and depend on for survival. Docking, life support reliability, and emergency response all become critical.

Salyut 1 was more than a symbol. It was meant to show the world that long duration habitation was possible, and it was also a platform for science and military experiments. But a space station is useless without people, and getting people there safely was the hard part. That is where Soyuz 11 came in…

Salyut 1 and the High Stakes of the First Space Station

Salyut 1 was a single module station, launched into low Earth orbit. It had docking hardware, living volume, scientific equipment, and a life support system designed for weeks. Compared to modern stations, it was small and primitive, but for 1971 it was a huge engineering project.

The Soviet plan was simple in concept but complex in reality. Launch the station, send a crewed Soyuz to dock, keep them there as long as possible, then bring them back. The goal was to prove endurance and gather medical data, plus demonstrate station operations like maneuvering, maintaining systems, and running experiments.

The first attempt to send a crew, Soyuz 10, did reach Salyut 1 and dock, but they could not enter the station due to a docking mechanism issue. That alone raised alarms. It showed that even if you reach orbit, the smallest mechanical mismatch can block the mission. A second attempt had to work, both for program confidence and for political pressure. Soyuz 11 was that second attempt…

The Crew of Soyuz 11 and Why They Were Chosen

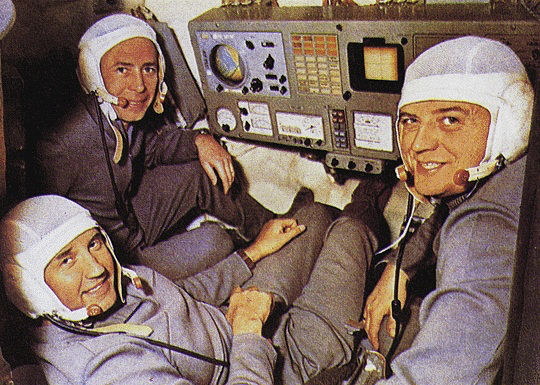

Soyuz 11 carried three cosmonauts, Georgy Dobrovolsky (commander), Vladislav Volkov (flight engineer), and Viktor Patsayev (research engineer). Their roles mattered because early space station flights required a mix of piloting, systems knowledge, and scientific work. They were expected to live aboard Salyut 1 for a long stretch, run experiments, and manage station operations under conditions nobody had fully mastered yet.

There is also an important piece of context that sometimes gets overlooked. The original prime crew for this mission was different. Shortly before launch, the prime crew was replaced due to medical concerns found during final checks. That switch meant the backup crew became the flying crew. This is not automatically bad, backup crews train hard, but it adds pressure and it can change how the final weeks of preparation feel. Procedures remain the same, yet the human factors, like familiarity with specific equipment quirks or personal comfort with last minute changes, can shift just a little…

Volkov was not new to space, he had flown before, giving the team valuable experience. Patsayev was deeply involved in technical and scientific tasks. Dobrovolsky as commander had the responsibility of leading decisions during docking, station work, and the complex return sequence. They were prepared for a demanding mission. What they were not prepared for was a failure mode that would happen fast, without a clear way to fight it.

The Soyuz Spacecraft Design and the Big Compromise

The Soyuz spacecraft is famous for being one of the most enduring human rated designs ever built. Variants of it have flown for decades. But early Soyuz versions were still evolving quickly, and the version used for Soyuz 11 had some design realities that directly influenced the outcome.

A Soyuz is divided into three main parts. There is an orbital module, a spherical living section used while in orbit. There is a descent module, the reentry capsule where the crew sits during launch and landing. And there is a service module, holding engines, fuel, power, and cooling systems. During reentry, the spacecraft separates, and only the descent module returns to Earth.

Here is the key compromise. The descent module was small. Fitting three people inside it was already tight. If the crew wore bulky pressure suits, it would be even tighter, and in that era, the Soviets chose to fly without full pressure suits on some missions in order to fit three cosmonauts. This was not done randomly, it was a tradeoff. More crew means more station work and more experiments, but no suits means a bigger risk if the cabin loses pressure.

Modern readers might think, why risk that at all. But remember, early human spaceflight was full of bold choices. Engineers believed the probability of a rapid depressurization in the critical phases was extremely low. The craft had been designed to be sealed, and the system that could vent the cabin was supposed to only open after landing. The idea seemed safe enough on paper. Sadly, the real world disagreed..

Launch and Docking, A Mission That Looked Successful

Soyuz 11 launched on June 6, 1971. Getting into orbit and approaching Salyut 1 required careful navigation, orbital adjustments, and precise timing. The spacecraft successfully docked with the station on June 7. That moment was historic. Humans had finally boarded the world’s first space station.

For over three weeks, the crew lived and worked inside Salyut 1. They performed scientific observations, tested station systems, and collected medical data on long duration spaceflight. In the early days of station operations, even normal living tasks were experiments. How does sleep change. How does appetite change. How does equipment behave after days of continuous use. How does ventilation move air in microgravity, preventing carbon dioxide pockets. These details matter a lot, and Soyuz 11 was gathering them in real time.

The crew also faced difficulties. Salyut 1 had issues with air quality and odor problems, likely tied to electrical equipment and the station environment. They had to manage fatigue and headaches, according to reports from the era. Still, the mission was considered a major achievement. The crew set a new endurance record for human spaceflight at the time, about 23 days. From the outside, Soyuz 11 looked like a victory for station living…

Undocking and the Start of the Return Trip

On June 29, 1971, it was time to return. The crew moved back into the Soyuz spacecraft, sealed hatches, performed checks, and undocked from Salyut 1. Undocking is not just backing away. It involves making sure the docking hooks disengage properly, confirming that station and ship systems are stable, and preparing for the engine burn that lowers the orbit for reentry.

After undocking, the spacecraft prepared for its deorbit burn. This burn is a controlled firing of the engine to slow the spacecraft down slightly, allowing gravity and atmospheric drag to pull it into a descent path. If the burn is too short, the craft can skip off the atmosphere. If too long, reentry can become steep and dangerous. Soyuz procedures were well developed by this time, but every mission still carried risk.

From telemetry and mission tracking, the return sequence appeared normal. The deorbit burn occurred, and the spacecraft entered the phase where it would separate into modules. This separation is a critical event. Explosive bolts or pyrotechnic devices fire, structural connections break, and the descent module becomes its own vehicle. After separation, it must orient correctly for atmospheric entry and deploy parachutes at the right altitude.

This is where Soyuz 11’s hidden problem begins. A small component, a pressure equalization valve, opened at the worst possible moment…

The Valve That Opened Too Soon

The cabin of a spacecraft is pressurized so humans can breathe. A normal space suit provides its own pressure environment, but the cabin does that job when suits are not worn. During landing, a spacecraft eventually has to equalize pressure with the outside air. Otherwise, after touchdown, opening the hatch would be difficult and could cause issues. To solve this, Soyuz had a valve system intended to open after landing, allowing outside air to enter gradually.

On Soyuz 11, during the module separation event, that valve opened early. This was not supposed to happen. Investigations concluded that a mechanical shock and the way separation forces interacted with the valve mechanism caused it to unseal. Some reports describe it as a design vulnerability in which a valve could be triggered by the separation process, especially if multiple pyrotechnic actions occurred in a certain timing.

Once the valve opened, air began to escape from the descent module into space. In orbit or high altitude, the outside pressure is near vacuum. When a pressurized cabin leaks into vacuum, pressure drops rapidly. How rapidly depends on the size of the opening, but in Soyuz 11’s case it was fast enough to become a life threatening emergency in a very short time..

The crew had no pressure suits to protect them. They did have procedures for leaks, but in the reentry phase, the ability to respond is limited. They were strapped in, handling transitions, and the leak rate was too high for slow fixes. To close the valve manually, they would have had to locate and actuate it under stress, in seconds, while experiencing a quickly changing environment. Even a small delay would make it harder to think clearly and coordinate.

One of the most haunting parts of Soyuz 11 is that the spacecraft itself continued to operate. Its automated systems kept the descent sequence going. It oriented, it deployed parachutes, and it landed, as if nothing unusual happened. The failure was inside, invisible to external observers until recovery teams opened the capsule…

What Ground Control Saw and Why It Was Hard to Diagnose

Spacecraft communications are not constant in all phases. During parts of reentry, signals can weaken or cut out due to plasma formation around the capsule. Even before the plasma blackout, the crew’s ability to transmit meaningful messages during a sudden emergency is limited by time and workload. A rapid depressurization also affects breathing and speech quickly.

Reports indicate that there was a loss of voice communication not long after separation. Ground controllers noticed abnormal signs, but they did not have an immediate clear explanation. Telemetry may show cabin pressure dropping, but interpreting it in real time, while also managing the normal reentry timeline, is tough. In that era, computers and displays were not as advanced as modern mission control systems. Also, if a system was believed to be highly reliable, controllers might first suspect sensor errors or communications issues.

There is also the brutal reality of timing. From separation to key reentry milestones, events happen quickly. Even if controllers understand what is happening, they cannot physically intervene fast enough. Commands take time to send, the craft is already in motion, and the crew must be the ones to take immediate action. With no suits, even a perfect diagnosis might not have changed the outcome..

It is important to describe this carefully. The Soyuz 11 disaster is not a story of people ignoring warnings. It is a story of a failure that occurred in a narrow window, with limited options, under the harsh physics of space. The crew were working within the limits of their spacecraft design.

Landing, Recovery, and the Shock on the Ground

The descent module landed in Kazakhstan on June 30, 1971, under parachute, on schedule. Recovery teams approached expecting a normal post landing scene. Typically, crews wave, open the hatch, and get medical checks. But when recovery personnel opened the capsule, they found that the crew were unresponsive.

Details in historical sources describe attempts by the recovery team to provide emergency aid, but without going into graphic descriptions, the key point is that by the time the capsule landed, the crew could not be revived. The cabin had lost pressure much earlier, during the high altitude phase, and survival without suits in that situation is not possible for long.

This moment had a huge psychological impact. A spacecraft landing safely is usually a sign that things went right. Soyuz 11 proved that a mission can appear successful from the outside while a fatal emergency happens inside. That lesson matters even today in aviation and spaceflight. You can have a working vehicle, but a failing environment for the humans within it…

The Investigation, Finding the Real Failure Mode

The Soviet program investigated intensely. They analyzed the descent module, its valves, separation mechanisms, and telemetry. They had to answer not just what happened, but why it was allowed to happen, and how to stop it forever. The conclusion centered on the pressure equalization valve opening prematurely during separation.

The valve was intended to open after landing, but the way it was actuated and protected was not robust enough against separation shock. Investigators also looked at whether the crew could have closed it. Evidence suggested they attempted actions consistent with responding to the leak, but the event progressed too fast to complete a fix. This is one of those hard truths in engineering, you can create a checklist, but if the system fails faster than a human can react, the checklist is not enough.

In space safety, engineers often talk about single point failures. That is a part which, if it fails, leads directly to loss of crew, without redundancy. The Soyuz 11 valve became a classic example. A single component, in the wrong state, could remove the cabin atmosphere. Once you recognize that, you redesign until that single point is gone or protected…

Another part of the investigation was the pressure suit decision. Flying without suits might be acceptable if the cabin is guaranteed sealed, but Soyuz 11 showed that guarantees are fragile. A tiny opening is all it takes. This forced a cultural shift. It was no longer enough to trust the cabin. The crew needed personal backup life support in the most dangerous phases, especially launch and reentry.

The Aftermath, Major Changes to Soyuz and Soviet Spaceflight

The consequences were immediate and long lasting. The Soviet Union paused crewed flights for a time to implement safety changes. One of the most significant outcomes was the introduction of pressure suits for launch and landing. The Sokol suit, developed for Soyuz crews, became standard. It was not a bulky moon suit, it was designed to fit the tight Soyuz descent module while still providing life saving pressure protection if the cabin depressurizes.

But that created a new problem. With suits on, fitting three people into the descent module was no longer practical. So early post Soyuz 11 Soyuz variants carried only two cosmonauts. This reduced station work capacity, but increased survival margins. It is a painful example of tradeoffs in spacecraft design, you can optimize for productivity or safety, but after a disaster, safety tends to become non negotiable.

The valve system was redesigned too. It had to be protected from accidental opening, with improved locking, redundancy, and better placement. Separation events were reviewed, and procedures were updated to ensure that pyrotechnic sequences did not create unintended forces on sensitive parts. In a way, Soyuz 11 made Soyuz stronger. The vehicle became a safer workhorse, partly because the program was forced to face a worst case scenario and rebuild around it…

There is also a broader shift. Space programs started paying more attention to what might happen during transitions, separation, staging, docking, undocking, reentry. These are moments where systems change state. A safe state in orbit might not be safe in separation, and vice versa. Soyuz 11 is a textbook case of a system that behaved correctly in its intended phase but entered the wrong state at the wrong time.

Why Depressurization is So Dangerous, The Simple Physics

Space is not empty in a poetic sense, it is physically hostile. At high altitudes above the atmosphere, there is essentially no air pressure. The human body is adapted to the pressure at Earth’s surface. When pressure drops sharply, the ability to breathe is immediately compromised, and oxygen in the bloodstream cannot be replenished. Even before you get into complicated medical effects, the simplest reality is that you cannot breathe without air pressure and oxygen supply.

This is why suits and cabin integrity are both essential. A spacecraft is like a tiny moving habitat. If that habitat loses pressure, it becomes unlivable almost instantly unless each person has a sealed backup environment. On missions where suits are worn, a cabin leak might still be serious, but it is not instantly fatal. On missions without suits, it can be.

Soyuz 11 also highlights another tricky part. If a leak is big enough, pressure can fall faster than a human can perform a mechanical action. That means safety needs to be automatic. Locking valves, redundant seals, sensors that trigger immediate closure, and suit requirements are all forms of automatic protection. Human reaction is valuable, but it cannot be the only defense…

The Human Side, What the Mission Achieved Before the Loss

It is easy to focus only on the disaster, but Soyuz 11 also achieved historic milestones. The crew were the first humans to live aboard a space station, proving that orbital habitation could last weeks. They gathered data on long duration living, physical changes, station operations, and the psychological side of being in a confined environment in orbit. They operated Salyut 1, tested equipment, and built knowledge that later stations would rely on.

This matters because later programs, including Mir and the International Space Station era, all benefited from early station lessons. Soyuz 11 showed that people can live in orbit for extended periods, but it also showed that the return phase is just as critical as the stay. You can do weeks of work, and still lose everything in minutes if a single system fails at the wrong time…

Remember too that space programs are made of humans, engineers, flight controllers, medical teams, and families. A disaster changes how people think. It can cause caution, fear, and also determination to improve. The safety culture that grew after events like Soyuz 11 was built on hard experience, not abstract theory.

Comparisons and Misunderstandings People Often Have

Sometimes people mix Soyuz 11 with other tragedies or assume it was a launch accident. It was not. The rocket worked, the docking worked, and the station phase was largely successful. The fatal event happened during the return, after deorbit burn, around the module separation period.

Another misunderstanding is that the crew had time to fully react and simply did not. In reality, rapid depressurization can remove usable time quickly, and the ability to locate, reach, and close a valve in a cramped capsule can be extremely hard. Spacecraft seats, straps, controls, and body positions are designed for reentry loads, not for suddenly standing up and reaching behind panels in seconds. This is why modern safety design avoids relying on last second human action for a fast failure mode…

People also ask why three crew were used at all if it meant no suits. The answer lies in mission goals. Salyut 1 needed a working team. More people meant more station tasks and more experiment time. It was a strategic choice for capability. After Soyuz 11, the cost of that choice became obvious, and the program adjusted.

The Lasting Legacy, How Soyuz 11 Shaped Modern Spaceflight

When you look at modern crewed vehicles, you can trace safety ideas back to Soyuz 11. Pressure suits for critical phases, careful valve design, redundancy, and an obsession with cabin pressure integrity are now standard. Even when spacecraft are considered very reliable, the suit provides an extra layer, a personal life support system that does not depend on the cabin being perfect.

The Soyuz spacecraft continued flying, and its later versions built a reputation for reliability. It became the transport workhorse for many station programs. That long legacy carries a strange contrast, one of the worst disasters helped make one of the most dependable spacecraft families in history. That is not comforting, but it is real..

Soyuz 11 also taught the world that a successful landing does not always mean a successful mission. Recovery teams, medical protocols, and post landing monitoring became more careful. Telemetry priorities changed. Programs began to treat cabin pressure and suit pressure as primary survival parameters, not just secondary engineering numbers.

In the end, the Soyuz 11 disaster is a reminder that space is not forgiving. It does not care about politics, schedules, or public image. A tiny opening can become a fatal problem. The response of engineers is to build layers, test assumptions, and redesign until a small failure cannot cascade into a catastrophe. That is the true lesson, and it is why studying Soyuz 11 still matters so much today…

Common Questions

Soyuz 11’s main goal was to dock with Salyut 1, the first space station, and keep a crew aboard for an extended stay. The mission aimed to prove long duration living in orbit, run experiments, and test station systems.

A pressure equalization valve, designed to open after landing, opened prematurely during the module separation phase. That allowed air to escape into near vacuum, dropping cabin pressure very fast.

At that time, the Soyuz descent module was too cramped to fit three cosmonauts wearing pressure suits. The design choice favored a three person crew for station work, assuming the cabin would remain sealed during launch and landing phases.

No, the descent module completed reentry and landed normally under parachute. The tragedy happened inside the capsule, and from the outside it looked like a standard landing.

Major changes included requiring pressure suits for launch and landing, redesigning the valve system to prevent accidental opening, and temporarily reducing crews to two to fit suited cosmonauts safely in the descent module.

It is a powerful example of how a small mechanical issue can become catastrophic, especially when combined with design compromises. It shaped modern safety rules around pressure suits, redundancy, and protecting cabin atmosphere integrity.

References & Further Reading

- NASA : 50 Years Ago: Remembering the Crew of Soyuz 11

- RussianSpaceWeb, mission details and technical background

- Wikipedia, Soyuz 11 (for quick cross checking of dates and names)

- Read about Challenger Disaster : CurioSpace

- Read about Energia Rocket, Russian SpaceShuttle : CurioSpace

- Read about SkyLab, The almost Disastrous Launch : CurioSpace