Dark Matter, The Invisible Backbone of the Universe

Introduction

Look up at the night sky and you see stars, planets, nebulae, galaxies, all the bright stuff. It feels like we are seeing the universe as it truly is. But here is the weird truth, most of the matter in the universe does not shine at all. It does not glow in visible light, it does not reflect sunlight, and it does not show up in normal pictures. Yet it still has gravity, and that gravity shapes almost everything we see…

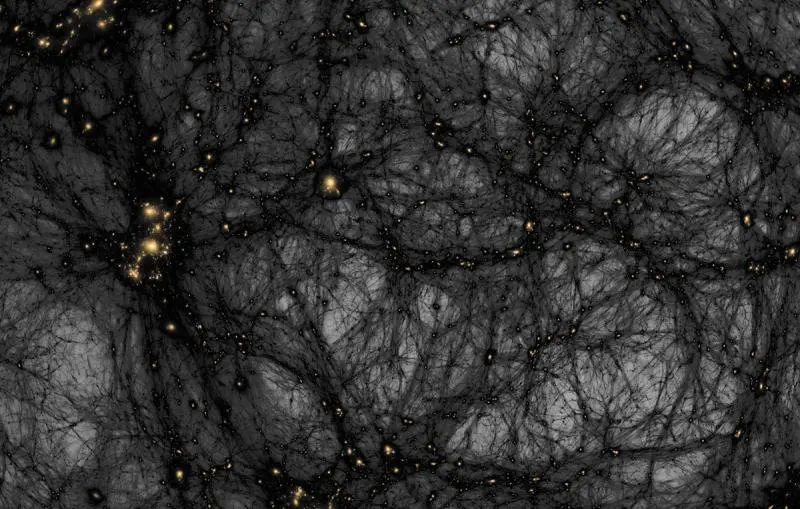

This invisible “something” is what scientists call dark matter. It is not a single confirmed object, at least not yet. It is more like a label for a mystery, we see its gravitational fingerprints everywhere, but we still do not know exactly what it is made of. Dark matter helps explain why galaxies rotate the way they do, why galaxy clusters stay together, and how the cosmic web formed across billions of years.

Since you already covered things like black holes, the Big Bang, quasars, and cosmic cannibalism in depth, this article will stay focused on dark matter itself. I will connect ideas lightly and link to your related posts where it makes sense, without repeating whole explanations.

What is dark matter, and what is it not?

Dark matter is matter that interacts mainly through gravity. That means it pulls on other matter, bends light through gravity, and helps structures form. But it does not interact much with light, at least not in a way we can easily detect. That is why it is “dark,” not because it is black colored, but because it does not emit or reflect light like normal matter.

It helps to also define what dark matter is not:

- Not dark energy. Dark energy is linked to the expansion of the universe, it is a different mystery.

- Not just “dust.” Dust blocks light, but dust is still normal matter, it glows in infrared and it behaves differently.

- Not simply black holes. Some black holes might contribute a little, but the leading explanations involve new particles.

- Not a sci fi fog. Dark matter is not something that floats around like smoke, it forms halos and structures because gravity organizes it.

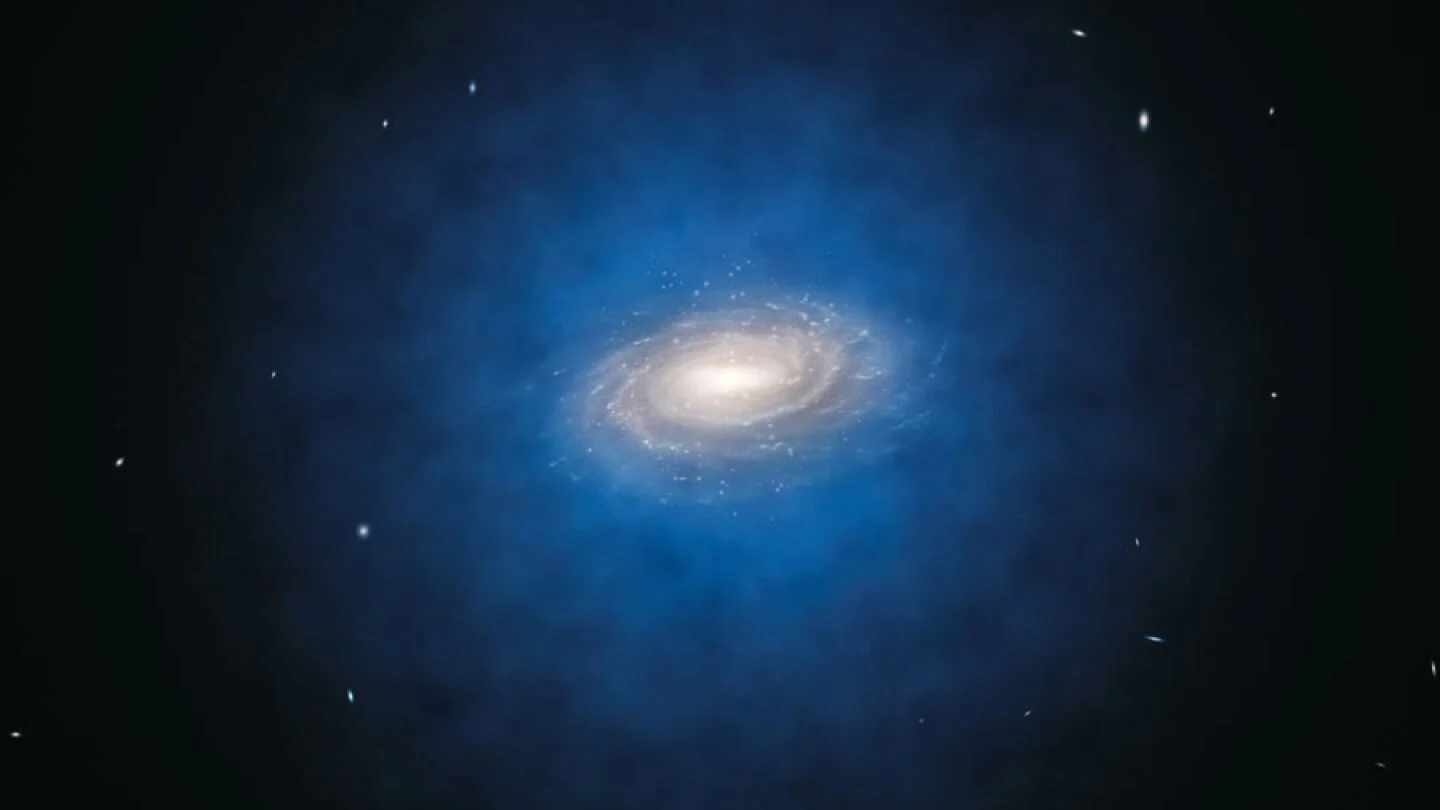

Dark matter is sometimes described as the scaffolding of the universe. Galaxies and clusters form inside dark matter “halos,” like lights decorating a frame you cannot see.

Related: If you want the basics of black holes in a separate, focused way, you already have it here, What is a Black Hole?

How did we even notice dark matter exists?

Dark matter was not discovered by a single photo or one dramatic moment. It showed up as a pattern of problems. Over time, those problems pointed to the same conclusion, there is extra mass out there that we cannot see.

1) Galaxy rotation curves

Galaxies rotate, stars orbit around the center. If a galaxy’s mass was mostly in the bright parts, we would expect stars farther out to orbit slower, similar to how planets move slower the farther they are from the Sun. But many galaxies do not behave like that. Instead, the outer stars often move surprisingly fast, as if there is a lot of extra mass in a wide, invisible halo around the galaxy.

That “missing mass” is one of the most famous clues. And it is not just one galaxy, it shows up again and again across many types of galaxies.

2) Galaxy clusters and “too much gravity”

Clusters of galaxies are massive, they have galaxies, hot gas, and more. When scientists measure how much gravity is needed to keep a cluster together, the visible matter falls short. Something invisible seems to add extra gravitational pull, otherwise the cluster would not stay bound the way it does.

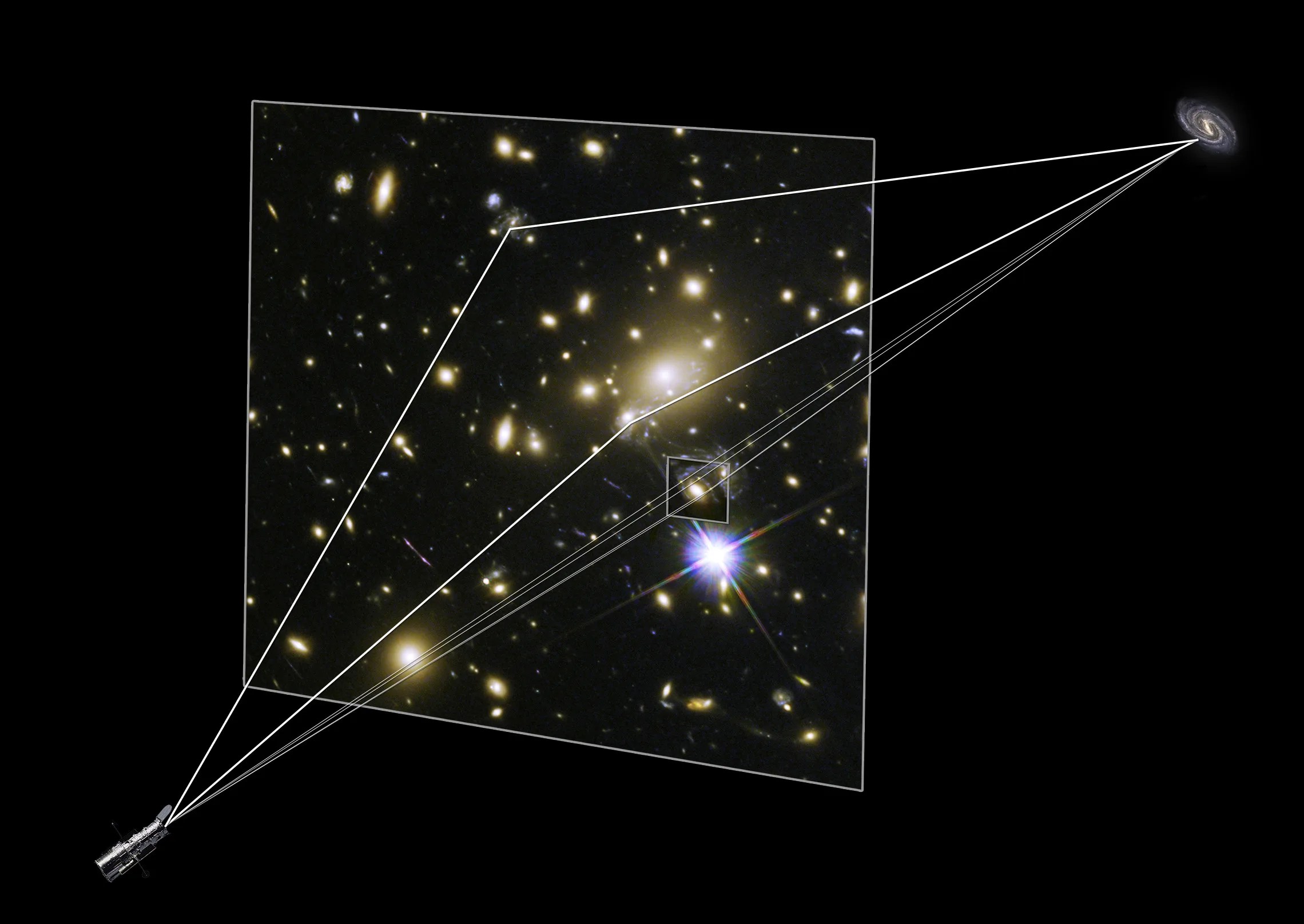

3) Gravitational lensing, light bends around unseen mass

Gravity bends light. So when a massive object is between us and a distant galaxy, the background light can warp, stretch, or even form arcs. This effect is called gravitational lensing. When astronomers map lensing in clusters, they often find the strongest gravitational regions do not match where the visible matter alone would suggest. It is like seeing a “mass map” that includes invisible weight.

4) The cosmic microwave background and the early universe imprint

The early universe left behind a faint “afterglow” called the cosmic microwave background. Tiny variations in that radiation, plus how galaxies are distributed today, match best with a universe that contains a lot of dark matter. In simple words, dark matter helped seed structure early, letting gravity build up matter into the cosmic web we see now.

Related: Your Big Bang article fits perfectly as background reading if someone wants the early timeline, Big Bang Explained, What Happened After?

Where is dark matter located?

Dark matter is not evenly smeared everywhere. Over cosmic time, gravity clumps it into structures. The most common picture is:

- Halos around galaxies, extending far beyond the visible disk

- Large halos around clusters of galaxies

- Filaments connecting clusters, forming a cosmic web

- Less dense voids where there are fewer galaxies and less mass overall

This matters because a galaxy is not just stars and gas. It is a bright center sitting inside a huge invisible halo. When galaxies interact and merge, it is not only the visible parts that collide, their dark matter halos overlap and reshape the system too.

Related: Galaxy merging and feeding is a great place to link your “cosmic cannibalism” article, Cosmic Cannibalism

What properties must dark matter have?

Even without knowing the exact particle, scientists can infer what dark matter is like from how it behaves on large scales.

- It has mass, because gravity depends on mass and energy

- It is mostly “collisionless”, meaning it usually passes through itself and normal matter without bumping or sticking much

- It does not emit light, or it would have been detected already in many cases

- It helped structures form early, which suggests it was present long before many stars formed

You might hear “cold dark matter” a lot. “Cold” here does not mean temperature like ice, it means the particles moved relatively slowly compared to the speed of light when structure was forming. Cold dark matter models match many observations, especially on large cosmic scales. There are also warm and hot versions, but they behave differently and do not match as well in many structure simulations.

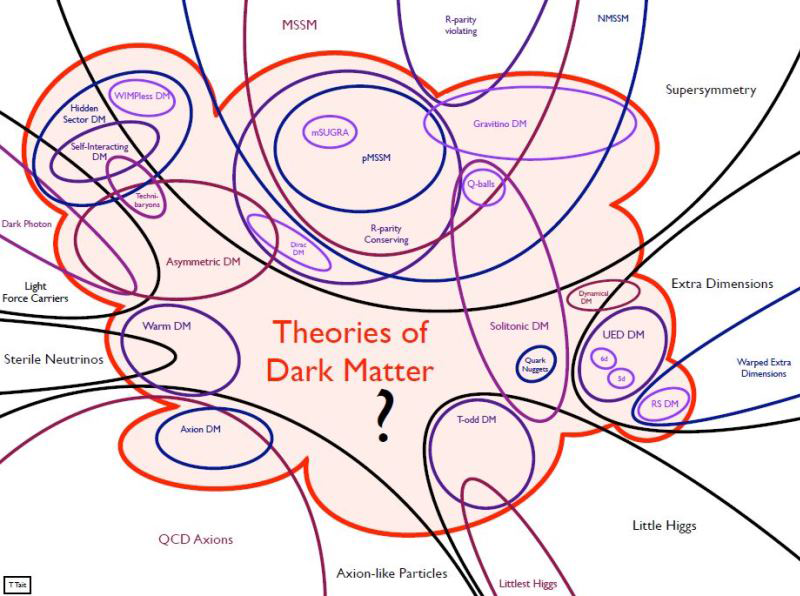

So what could dark matter actually be made of?

This is where things get exciting, and also annoying, because we still do not have a confirmed answer. But there are leading candidates that fit the required behavior.

1) WIMPs, the classic candidate

WIMPs stands for Weakly Interacting Massive Particles. The name basically says what they are, heavy particles that barely interact with normal matter. For a long time, WIMPs were a favorite because they can naturally appear in some physics models, and they can produce the right amount of dark matter in the early universe.

But so far, direct searches have not confirmed them. That does not fully rule them out, it just means dark matter might be trickier than the simplest version of WIMPs.

2) Axions, very light but very real (maybe)

Axions are extremely light particles proposed for reasons connected to particle physics. If they exist, they could be abundant enough to account for dark matter. Axions are hard to detect because they interact extremely weakly, but there are experiments designed specifically to search for them.

3) Sterile neutrinos, a quiet cousin

Normal neutrinos exist, but they are too light to make up most dark matter. Sterile neutrinos are a hypothetical kind that would interact even less than normal neutrinos. Depending on their mass, they could behave like warm dark matter. This idea has ups and downs, and it is still debated.

4) MACHOs and “normal but faint” objects

MACHOs are Massive Compact Halo Objects, like faint stars, brown dwarfs, and other dim objects. These are normal matter. They might exist in halos, but measurements suggest they cannot account for most of the dark matter. Basically, there is not enough of them to explain the full gravitational effect.

5) Primordial black holes, a side possibility

Some theories suggest that black holes formed very early, long before stars, could account for some fraction of dark matter. This is interesting, but it is constrained by several observations. It might contribute a little, but it probably is not the whole answer. And you can link black holes separately without repeating details.

How do scientists try to detect dark matter?

Since dark matter does not shine, detection is about catching rare interactions, or seeing indirect signatures. There are three big approaches.

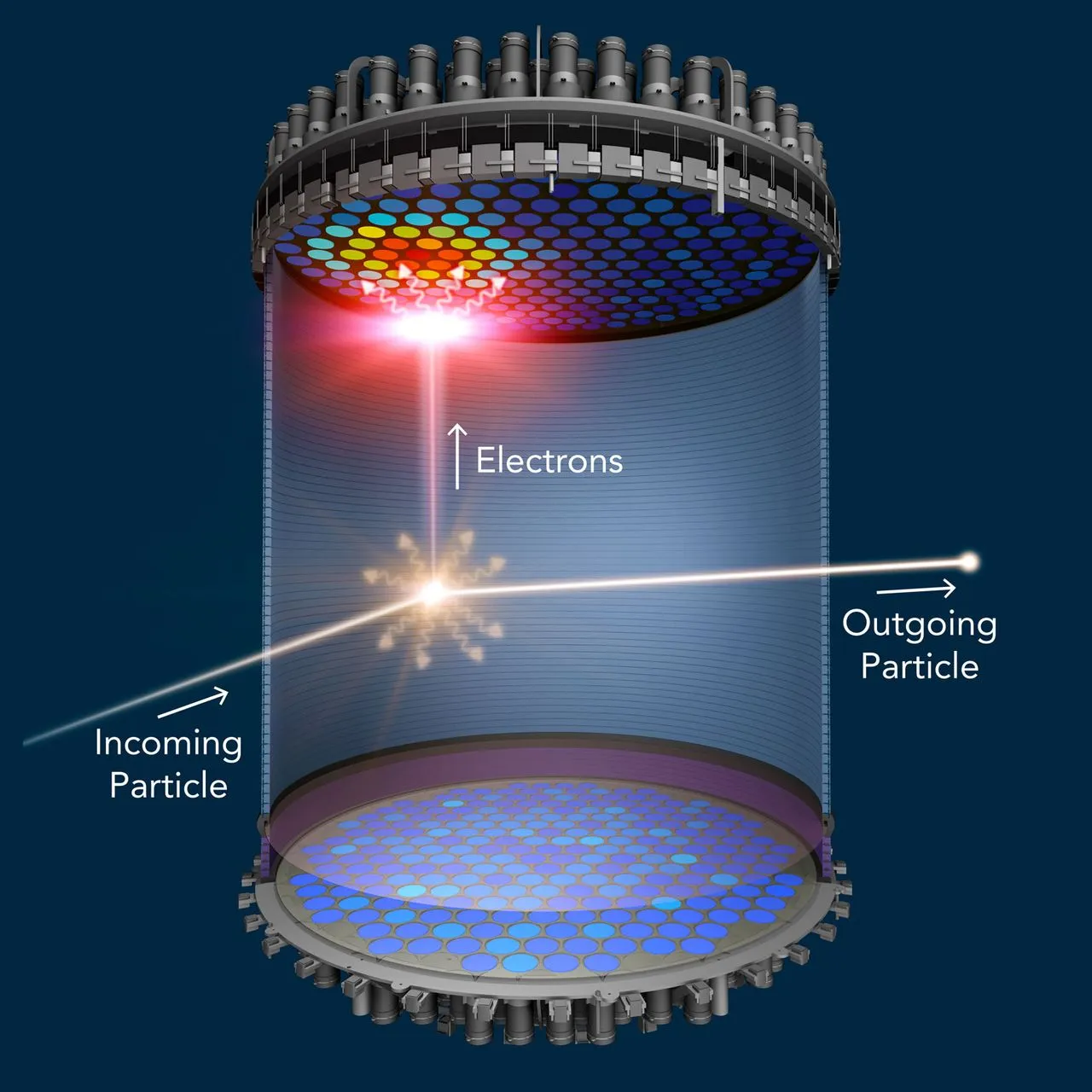

1) Direct detection

These experiments look for a dark matter particle hitting a normal atom, creating a tiny recoil. The challenge is huge, you need incredibly sensitive detectors, deep underground, with heavy shielding, because background noise can easily fake a signal.

2) Indirect detection

If dark matter particles can annihilate or decay in rare ways, they might produce gamma rays, neutrinos, or other particles. Observatories search for unusual excesses from regions rich in dark matter, like the center of galaxies or dwarf galaxies. The hard part is separating a real dark matter signal from ordinary astrophysical sources.

3) Collider searches

In high energy particle colliders, scientists smash particles together and look for missing energy and momentum. If new invisible particles are produced, they would not be directly seen, but their existence can be inferred. Collider hints are complicated though, because many processes can mimic missing energy signatures.

None of these approaches has delivered a confirmed discovery yet, which is why dark matter remains one of the biggest open problems in modern physics and astronomy.

Could it be that gravity itself needs fixing?

Some alternatives suggest that the “missing mass” problem is not dark matter, but our understanding of gravity breaking down on galactic scales. Modified gravity ideas can explain some galaxy rotation curves, especially in certain cases. But many observations, like cluster lensing patterns and large scale structure, are difficult to explain with modified gravity alone, without reintroducing something that behaves a lot like dark matter anyway.

So for now, dark matter remains the leading explanation because it fits multiple independent lines of evidence with one consistent picture.

Dark matter vs dark energy, quick difference

This confusion is super common, so it is worth a short clear section.

- Dark matter pulls things together through gravity, it helps form galaxies and clusters.

- Dark energy is linked to the accelerated expansion of the universe, it acts like a push on the largest scales.

They are both “dark” because they are not directly seen, but they are not the same thing at all.

How dark matter shapes galaxies, without stealing the spotlight

Dark matter does not build stars by itself, but it sets the stage. In the early universe, dark matter clumped first, creating gravitational wells. Normal matter, like gas, fell into those wells, cooled, and eventually formed stars and galaxies. This is why dark matter is sometimes called the backbone of structure.

This also helps explain something interesting, galaxies do not form randomly. They trace the dark matter distribution. Where dark matter is dense, galaxies are more likely to form. Where it is sparse, you get large cosmic voids.

And when galaxies merge, the dark matter halos merge too. That gives you a nice link opportunity to your merger focused content. If someone is reading about cosmic cannibalism, dark matter halos are part of the unseen story happening behind the bright fireworks.

Related: For a different kind of extreme cosmic engine, your quasar article fits as a “deep dive” link, Quasars Explained, Brightest Beacons of the Universe

Common misconceptions, cleared up fast

- “Dark matter is antimatter”, not really. Antimatter interacts with light and normal matter strongly, it would not stay hidden.

- “It is just empty space”, no, space can be empty, but dark matter has gravitational mass.

- “We made it up to fix equations”, the evidence comes from different methods, rotation curves, lensing, early universe signals, structure growth, all pointing to the same missing mass picture.

- “It is inside black holes”, black holes are part of the universe’s mass, but dark matter appears distributed as halos and filaments, not only as compact objects.

What comes next?

The next progress will probably come from a combination of better sky surveys and better detectors. Mapping weak lensing across huge areas, measuring how galaxies cluster, watching how structures grow over time, all of that tightens the net around what dark matter can be. Meanwhile, lab experiments keep pushing sensitivity to new levels, trying to catch even a whisper of interaction.

Even if dark matter turns out to be a particle we have never seen before, that would be a massive discovery, not only for astronomy, but for physics as a whole. It would mean the Standard Model is incomplete in a very real, measurable way. If instead we discover a more complex story, like multiple components or unusual interactions, that is also big. Either way, the universe is holding a card we have not flipped yet…

Final thoughts

Dark matter is one of those topics that feels almost unfair. It shapes galaxies, bends light, and controls the architecture of the cosmos, but it refuses to show itself directly. Still, the evidence for its gravitational presence is strong, and the search for its identity is one of the most important scientific hunts happening today.

If you remember one simple idea, remember this, dark matter is not what we see, it is what we infer from how the universe moves and holds together. The visible universe is the decoration, dark matter is the framework behind it…

Common Questions

Because it does not emit or reflect light in an easy detectable way. It is “dark” to telescopes, but not invisible to gravity..

No. Dark matter pulls things together and helps form structure. Dark energy is linked to the universe expanding faster over time.

Because we can measure its gravitational effects, galaxy rotation speeds, gravitational lensing, cluster dynamics, and early universe signals all point to extra mass.

Some compact objects could contribute a small part, but most evidence suggests the majority is not made of normal faint objects. Particle candidates are still the main focus.

There is no confirmed “best” yet. WIMPs and axions are popular, but many ideas are still being tested because we do not have a direct detection.

It is hard to predict. Experiments and surveys are improving fast, but dark matter might interact so weakly that it takes time. The good news is that each new result narrows the possibilities..