Touching the Sun, The Parker Solar Probe’s Historic Mission

Introduction

Look up at the sky on a clear day and you see it. Our Sun. That constant, reassuring presence. For most of history, it was a disk, a symbol, a mystery observed from afar with awe and a little fear. Today, for the first time, humanity is not just looking. We are touching. We have a piece of our own ingenuity, a spacecraft named Parker, flying through the Sun’s atmosphere itself. This is the story of that audacious journey, a tale of seventy-year-old questions, brilliant minds, and engineering so tough it can stare into a stellar furnace and not blink.

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe isn’t just another satellite. It’s arguably the boldest mission of robotic exploration ever attempted. It is the closest object humanity has ever sent to our star, and with each daring loop, it’s rewriting the textbooks. But why take such an insane risk? The answer is in your pocket and powering your home. Our modern world is terrifyingly vulnerable to the Sun’s tantrums, to “space weather.” Solar storms can fry satellites, disrupt grids, and endanger astronauts. Parker is our scout, sent into the storm to understand its origin, fundamentally to protect our civilization. This is more than science, it’s planetary defense.

The Puzzling Paradoxes That Drove the Mission

For centuries, our knowledge of the Sun was built on distant observations. We mapped its surface, the photosphere, with temperatures around 5,500°C. Yet during solar eclipses, a stunning paradox emerged: the Sun’s wispy outer atmosphere, the corona, shimmered with heat exceeding a million degrees Celsius. How could the atmosphere be hundreds of times hotter than the surface below? This “coronal heating problem” has been one of the great unsolved puzzles in all of astrophysics for nearly a century. It defies basic intuition, like the air around a flame getting hotter as you walk away.

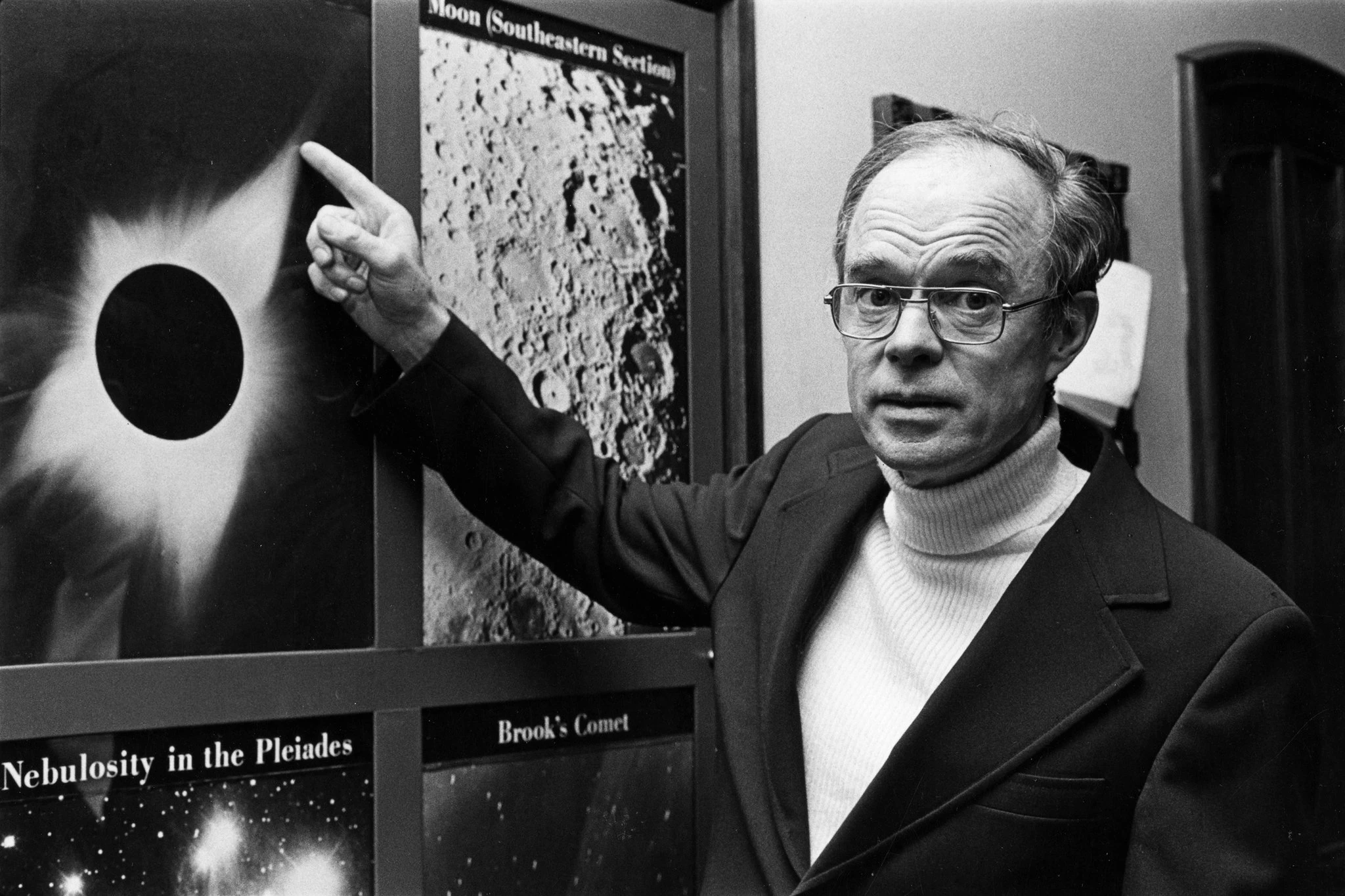

Then there was the solar wind. In the 1950s, a young scientist named Eugene Parker proposed a radical idea. He said the Sun’s corona was expanding, constantly blowing a stream of charged particles outward. He called it the “solar wind.” The idea was initially rejected and laughed at, but soon, satellite measurements proved he was brilliantly right. This wind is what fills our solar system and buffets Earth. But the “how” was a mystery. Where does this wind get its speed? We’ve been measuring it from near Earth for decades, but that’s like studying a river by dipping a cup in it a hundred miles from its source. You miss all the action. Parker the probe was conceived to go to the headwaters.

A Dream Named Parker, From Concept to Reality

The idea of a solar probe was born in the think tanks of the late 1950s, right alongside the dawn of the space age. But for over half a century, it remained a dream on paper. The technology to protect a spacecraft that close to the Sun simply didn’t exist. How do you build a camera, a computer, a wire, that can survive that?

The breakthrough came with material science. A new kind of heat shield, made from a revolutionary carbon-carbon composite, began to look possible. This wasn’t just a slab of metal. It was a high-tech sandwich, light but incredibly strong, designed not just to resist heat, but to reflect it and reradiate it back into space. With this shield as a foundation, the mission, then called Solar Probe Plus, finally got the green light.

Then, in a beautiful and rare move, NASA decided to honor the man whose theory started it all. In 2017, they renamed it the Parker Solar Probe, after Dr. Eugene Parker, then a lively 90-year-old. It was the first, and so far only, time NASA has named a mission for a living person. When the probe launched on August 12, 2018, from Cape Canaveral atop a thunderous Delta IV Heavy rocket (one of the few powerful enough to send it on its difficult path), Dr. Parker was there to watch. A moment of pure, human poetry in the story of science.

Building a Ship for Hell, The Engineering Marvel

So, what does it take to build a ship that can touch the Sun? Let’s talk about the challenges, because they are mind-boggling.

First, there’s the heat. At its closest point, about 4 million miles from the solar surface, the intensity of sunlight is over 500 times what we feel on Earth. The heat shield facing the Sun will reach temperatures of nearly 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit. Hot enough to melt steel. Then there’s the radiation. The Sun is a constant nuclear furnace, and flying this close means bathing in a flood of high-energy particles that can scramble electronics. And finally, there’s the speed. To get that close to the Sun’s immense gravity, Parker has to fall *incredibly* fast. At its fastest, it’s traveling at over 430,000 miles per hour. That’s fast enough to get from New York to Tokyo in under a minute. At that speed, running into even a tiny speck of dust is like a high-caliber bullet impact.

The answer to all this is the Thermal Protection System, the TPS. That’s the heat shield. It’s an 8-foot diameter disk, about 4.5 inches thick, made of two panels of superheated carbon-carbon composite with a light, insulating foam core. The Sun-facing side is coated with a special ultra-white ceramic paint. The magic is in its efficiency. While the front glows cherry red, the spacecraft body huddles in its shadow, where the temperature is a comfortable, almost room-temperature 85 degrees Fahrenheit. All the delicate instruments live back there, in this manufactured oasis of cool.

But the shield only works if it’s always pointing perfectly at the Sun. A single mistake, a slight misalignment, and sunlight would creep around the edge and fry the spacecraft in seconds. So Parker has to be smart, and autonomous. It has tiny, simple sensors, called solar limb sensors, mounted along its edge. If one of them sees the Sun, it means the probe is turning the wrong way. Its brain instantly recognizes this and fires small thruster jets to correct itself, all without waiting for a command from Earth, which by that point would be 8 minutes too late. It literally has to save its own life, over and over again.

The Instruments, Senses in the Inferno

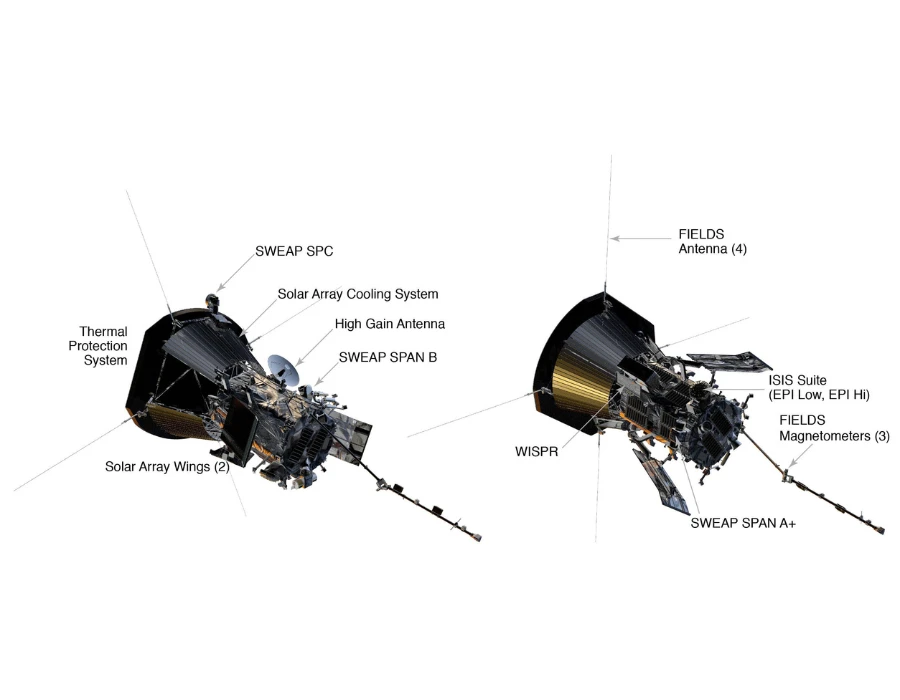

Packed behind that shield are four suites of instruments, each designed to answer a piece of the puzzle.

FIELDS: This is the mission’s magnetometer and plasma wave detector. It has antennas that stick out, carefully, from behind the shield to measure the Sun’s electric and magnetic fields directly. Think of it as taking the pulse of the Sun’s magnetic heartbeat. This is key to understanding how energy is transferred.

SWEAP: The Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons investigation. This is the wind collector. It has two instruments. One, called the Solar Probe Cup, is a truly brave little device. It’s a small metal cup that actually sticks out *past* the heat shield into the direct sunlight. It faces the solar wind head-on, counting and measuring the particles as they stream past. The fact it doesn’t instantly melt is a testament to its design. SWEAP tells us what the solar wind is made of, right at the source.

ISʘIS: The Integrated Science Investigation of the Sun (the symbol in the middle is a Sun symbol). This one catches the bad guys, the really energetic particles that get accelerated to near light-speed during solar storms. These particles are a major radiation hazard, and ISʘIS figures out where they come from and how they get so much energy.

WISPR: The Wide-field Imager for Parker Solar Probe is the only actual camera on board. But it’s not pointed at the Sun’s blinding surface. It looks out sideways, capturing images of the corona and solar wind structures ahead of the spacecraft. Its view from *inside* the corona is revolutionary. It’s like being inside a snowstorm for the first time, instead of just watching it through a window.

The Long Road In, The Venusian Dance

Here’s another counterintuitive fact, going to the Sun takes a lot of time and a very indirect route. You can’t just aim a rocket at it and fire. Because Earth itself is moving sideways around the Sun at 67,000 miles per hour, anything launched from Earth carries that sideways speed. To fall into the Sun, you have to cancel out *all* of that motion. That requires an impossible amount of rocket fuel.

So Parker uses a clever, gravity-assisted trick. It’s flying a series of ever-tightening loops around the Sun, and on each loop, it gets a gravity assist from… Venus. Yes, the planet Venus. Over its seven-year primary mission, Parker will swing by Venus seven times. As it passes close to the planet, Venus’s gravity acts like a brake, stealing a tiny bit of the probe’s orbital energy. This slows Parker down just enough that on its next pass, the Sun’s gravity pulls it in even closer. Each Venus flyby shrinks the orbit, like a spiral staircase leading down to the solar surface. It’s a beautiful, slow, and incredibly precise celestial dance that requires perfect timing and navigation.

What We’ve Learned So Far, Mind-Bending Discoveries

The data has been flowing back for years now, and it has already turned solar science on its head.

The biggest headline is the discovery of “switchbacks.” These are bizarre, sudden flips in the Sun’s magnetic field. Imagine the magnetic field lines are like highways for particles. Close to the Sun, Parker found that these highways aren’t straight. They have giant, S-shaped kinks in them, where the magnetic field suddenly reverses direction and then whips back again. These switchbacks are huge, and they are filled with energetic particles. They seem to be a fundamental feature of the solar wind near its origin, and they might be a key piece of the puzzle for how the corona is heated and the wind is accelerated. They were a complete surprise.

In December 2021, Parker achieved its core mission objective. It officially “touched the Sun.” Scientists determined it crossed a boundary called the Alfvén critical surface. This is the point where the Sun’s magnetic field and gravity are no longer strong enough to hold onto its plasma, and the material officially becomes the solar wind, flowing freely away. For the first time, a human-made object was inside the Sun’s atmosphere, sampling the birthplace of the solar wind. The data from inside showed the corona isn’t a smooth, uniform layer. It’s structured and dynamic, with spikes and valleys where the magnetic field creates pockets of slower, denser material.

It also confirmed the existence of a theorized “dust-free zone.” The inner solar system is full of fine dust from comets and asteroids. Parker’s images and impacts showed that very close to the Sun, this dust disappears, likely because the intense heat vaporizes it. This creates a relatively clear region around the star, which was predicted but never before confirmed.

The Legacy, Why This All Matters for Us

Okay, so we’ve solved some cosmic puzzles. That’s great for scientists in labs. But what does it mean for the rest of us, down here on Earth?

Everything. Every new data point from Parker gets fed into complex computer models that simulate the Sun’s behavior and predict space weather. Before Parker, these models were making educated guesses about what was happening in the corona. Now, they have ground truth, real measurements from the scene. This is leading to a revolution in our forecasting ability. Our goal is to get to a point where we can predict a major solar storm days in advance, with high accuracy, just like we predict a hurricane.

With that warning, satellite operators can put their multi-billion dollar assets into safe mode. Power grid companies can prepare their systems to handle the surging currents. Airline pilots on polar routes (which are more exposed) can be rerouted to lower radiation altitudes. Future astronauts on their way to the Moon or Mars can take shelter in shielded compartments of their spacecraft. Parker’s mission is fundamentally about resilience. It’s about making sure that as our civilization grows more complex and woven into the fabric of space, we are not undone by the very star that gives us life. The data is also teaching us fundamental physics about how stars work, knowledge that applies across the universe.

The Journey Continues

As of right now, the Parker Solar Probe is still out there, healthy and strong, its mission extended through 2025. It continues its silent, blistering loops around the Sun, diving closer than ever before on each pass. Each new orbit is a record-setter, for speed and for proximity. It works in concert with other missions, like the European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter, which provides a different, complementary perspective. Together, they are building the most complete picture of a star in the history of astronomy, our own.

The story of Parker is a human story. It’s the story of Eugene Parker’s stubborn brilliance in the face of rejection. It’s the story of engineers who spent decades solving a problem that seemed impossible. It’s the story of scientists whose patience is now being rewarded with discoveries they only dreamed of. It reminds us that the biggest mysteries are often right in front of us, lighting up our sky every single day. And it proves that with enough curiosity, courage, and sheer technical grit, humanity can reach out and touch the fire, and in doing so, learn how to live safely in its light for generations to come. Not bad for a little probe named Parker.

Common Questions

It doesn’t melt because of its revolutionary heat shield, the Thermal Protection System (TPS). This shield, made of carbon-carbon composite, reflects and reradiates the immense heat. While the front faces temperatures near 2,500°F, the spacecraft body hides in its shadow, where it’s a cool 85°F.

Switchbacks are sudden, giant S-shaped kinks or reversals in the Sun’s magnetic field, discovered by Parker. They are filled with energetic particles and are a dominant feature near the Sun. They’re important because they likely hold a key to understanding how the solar wind is accelerated and how the corona is heated, solving two major mysteries.

Yes, it holds the record. At its closest approach (perihelion), the Sun’s gravity accelerates Parker to over 430,000 miles per hour (about 700,000 km/h). That makes it the fastest human-made object in history by a wide margin.

In December 2021, Parker crossed the Alfvén critical surface. This is the boundary where the Sun’s atmosphere ends and the solar wind begins. By crossing this boundary, the spacecraft became the first to enter the Sun’s corona, or atmosphere and literally “touching” the material of the Sun itself.

It uses Venus’s gravity as a brake. Each of its seven flybys slows the probe down a bit, allowing the Sun’s gravity to pull it into a tighter, closer orbit. This “gravity assist” method is an energy-efficient way to get close to the Sun without carrying an impossible amount of fuel from Earth.

By understanding the origins of solar wind and storms, scientists can vastly improve space weather forecasts. This gives us crucial warning to protect satellites, power grids, GPS, and astronauts from damaging solar eruptions, safeguarding our technology-dependent society.

References & Further Reading

- NASA: Parker Solar Probe Mission Page

- Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab: Parker Mission Site

- Wikipedia: Parker Solar Probe

- Space.com: The Dangers of Space Weather

- Learn About the Voyager Probes : CurioSpace

- Learn About Apollo 11, First Touched down at Moon : CurioSpace

- Learn About Project Gemini : CurioSpace