Pluto: The Little World That Refused to Stay Small

Let me take you back to a time when the solar system had exactly nine planets and nobody, literally nobody, ever questioned it. For seventy-six straight years Pluto sat comfortably at the end of the list, the smallest, the coldest, the farthest, yet still family. We drew it in crayons, we coloured it light blue or purple, we stuck it on every classroom wall chart right after Neptune. Then one random morning in August 2006 the grown-ups in Prague decided the rules had changed, and just like that Pluto was out. A lot of us who grew up in the 90s or early 2000s still remember the exact moment we heard the news, many of us were told in school that Pluto was suddenly “gone” with zero proper explanation, and yes, more than a few of us spent years quietly convinced that planets could simply explode or vanish one by one. Turns out that confusion was shared by an entire generation, but today we are here to set the record straight, once and for all, with the complete, honest, mind-blowing story of Pluto, the world that refused to be forgotten no matter what label we stick on it.

The discovery: how a farm boy from Kansas found the ninth planet

February 18, 1930. Clyde Tombaugh was twenty-four years old, raised on a wheat farm in Illinois, no college degree, just a handmade telescope and an obsession with the stars. He got hired by Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, because his drawings of Mars and Jupiter impressed the director. His actual job was mind-numbing: take two huge glass plates of the sky weeks apart, put them in a machine called a blink comparator, flip back and forth rapidly, and look for anything that moved. He did that night after night for almost a full year. On that February evening the tiny dot finally appeared, shifting just enough against the background stars to prove it was in our solar system. Planet X, the mysterious world Percival Lowell had spent a fortune searching for, had finally been found by a self-taught kid who still smelled like Kansas soil.

The announcement made front pages everywhere. The observatory was flooded with name suggestions, some serious, some ridiculous. An eleven-year-old schoolgirl in Oxford, England, Venetia Burney, was having breakfast with her grandfather when she heard the news on the radio. She told him the new planet should be called Pluto because it was dark and far away, just like the god of the underworld. Her grandfather, a former librarian at Oxford University, happened to know a professor who knew someone at the observatory. The name reached Arizona, the staff voted unanimously, and on May 1, 1930, Pluto became official. From that moment on it belonged to every child who ever learned the order of the planets.

Seventy-six years of pure childhood happiness

For three entire generations the solar system was perfectly simple: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Pluto. Every single poster, every single mobile hanging over cribs, every single science textbook ended with those nine names. We invented mnemonics that still live in our heads decades later, My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nine Pizzas, or the slightly ruder versions we whispered on the playground. Disney released Mickey’s dog Pluto the same year the planet was discovered, cementing the name in pop culture forever. Pluto became the ultimate underdog, the little guy who made it into the club despite being tiny, cold, and ridiculously far away. Nobody ever imagined that membership could be taken away.

Then the 1990s arrived and everything quietly started to crack. Better telescopes and bigger surveys began spotting objects beyond Neptune, hundreds, then thousands of icy bodies in a huge doughnut-shaped region we now call the Kuiper Belt. Many were respectable in size. In 2005 Mike Brown and his team at Caltech discovered Eris, an object 27 percent more massive than Pluto and almost the same size. Suddenly the question nobody had ever needed to ask became impossible to ignore: if Pluto is a planet, why isn’t Eris? And what about Haumea, Makemake, Quaoar, Sedna, and the dozens more we kept finding? The old definition, basically “we call these eight big ones planets and Pluto because tradition”, was no longer enough.

The Prague vote that broke a billion hearts

August 2006, Prague, Czech Republic. The International Astronomical Union was holding its once-every-three-years general assembly. For the first time ever they decided to write an official definition of the word “planet”. After days and days of arguments, late-night bar debates, and countless drafts, they settled on three requirements:

1. It must orbit the Sun directly

2. It must have enough mass to pull itself into a nearly round shape (hydrostatic equilibrium)

3. It must have cleared its orbital zone of other objects of similar size

Pluto sails through the first two with no problem. It orbits the Sun and it is beautifully spherical. But the third rule is brutal. Pluto’s orbit is crowded with thousands of other Kuiper Belt objects, some almost as big as Pluto’s moons. It has never cleared its neighbourhood. On August 24, 2006, only about 424 astronomers out of roughly ten thousand IAU members were still in the room (many had already left for the airport), but they took the vote anyway. Pluto lost. A brand-new category was invented right there on the spot: dwarf planet.

The reaction was immediate and ferocious. Children cried on American morning news shows. Newspapers around the world ran headlines screaming “Pluto Demoted”. Online petitions collected hundreds of thousands of signatures in days. The state of New Mexico, where Clyde Tombaugh had lived and worked, passed an official resolution declaring that Pluto is still a planet any time it is visible in New Mexico skies. Illinois, Tombaugh’s home state, followed with its own symbolic law. Late-night talk shows made jokes, but the pain was real. An entire generation had grown up with nine planets and suddenly the universe felt a little colder.

Why the decision actually makes scientific sense (even though it still hurts)

Put emotion aside for a second. If we had kept Pluto as a planet we would have been forced to add Eris, Haumea, Makemake, Sedna, Gonggong, Quaoar, and probably dozens more in the coming decades. We would end up with fifty, seventy, maybe a hundred planets, most of them tiny frozen worlds that look almost identical. The word “planet” would stop being useful. The IAU wanted eight dominant worlds that gravitationally rule their orbits and everything else in cleaner categories. It is consistent, it is logical, and it is terrible at public relations.

2015: the flyby that brought Pluto back to life

July 14, 2015, 11:49 UTC. After a journey of nine and a half years and almost five billion kilometres, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, about the size of a grand piano, raced past Pluto at more than 49,600 kilometres per hour. It had only one shot, no orbit, no second chance. The data took sixteen months to download completely because the spacecraft was so far away.

The first close-up images arrived and the entire planet Earth stopped breathing for a moment. The most iconic feature is Tombaugh Regio, the enormous heart-shaped plain of frozen nitrogen bigger than Texas, bright and smooth and almost crater-free. There are jagged mountain ranges made of hard water ice rising three to four kilometres high, yet they float like icebergs on softer nitrogen ice underneath. There are bizarre bladed terrains that look like giant knife edges, there are possible cryovolcanoes taller than anything on Earth that may still erupt ice and slush, there are dark red patches covered in complex organic molecules, and there is a thin haze layer that scatters sunlight to produce a stunning blue sky at sunset.

Scientists were completely unprepared for this level of activity. Alan Stern, principal investigator of the mission, said live on television, “We have a new definition of what a planet can be… Pluto is alive.” The frozen dead rock we imagined for decades turned out to be one of the most geologically diverse and active worlds we have ever seen.

Pluto by the numbers (prepare to be shocked)

Diameter: 2,376 kilometres, less than one-fifth the size of Earth, smaller than seven moons in our solar system including our own

Mass: only 0.0022 Earth masses, you could fit 472 Plutos inside Earth

Surface gravity: 0.063 g, a 70 kg person would weigh about 4.5 kg there

One day (rotation period): 6.387 Earth days, it spins backwards compared to most planets

One year (orbit): 248 Earth years, Pluto has completed less than one full lap since its discovery

Average surface temperature: −229 °C, cold enough that nitrogen freezes solid

Distance from Sun: 29.7 to 49.3 AU (4.4 to 7.4 billion kilometres), sometimes closer than Neptune

Orbital eccentricity: 0.248, the most elliptical orbit of any large body in the solar system

Orbital inclination: 17.14 degrees, way off the flat plane where the eight planets live

Atmosphere: mostly nitrogen with methane and carbon monoxide, only 1/100,000th the pressure of Earth’s air

Density: 1.86 g/cm³, about 60 percent rock and 40 percent ice, more like a giant comet nucleus than a rocky planet

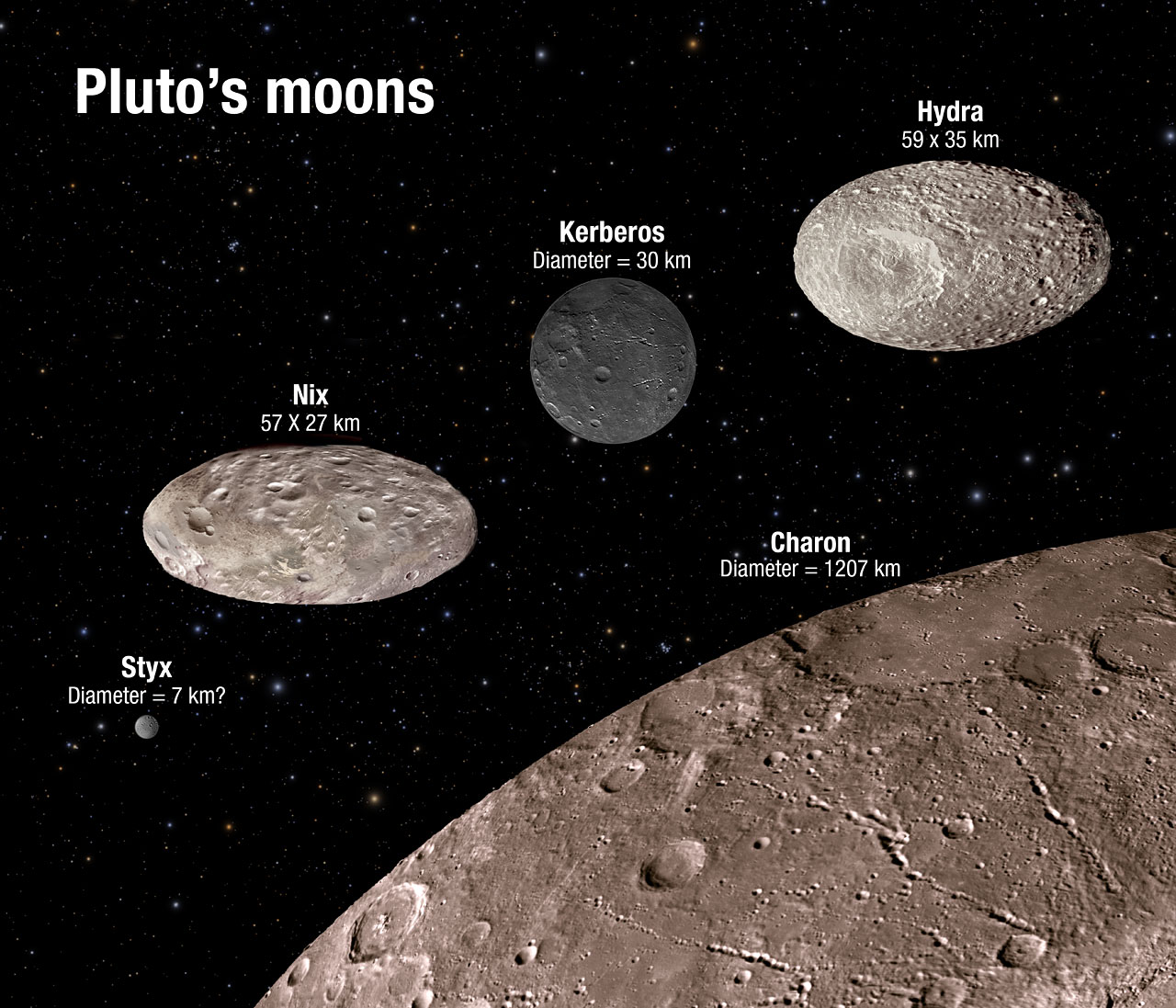

The five moons and the eternal dance with Charon

Pluto is not a lonely world. It has five known moons, and the biggest one, Charon, is extraordinary. Charon is 1,212 kilometres across, more than half Pluto’s diameter. The centre of mass of the system lies outside Pluto itself, so technically both worlds orbit a point in empty space. They are tidally locked, each always showing the same face to the other, forever staring into each other’s eyes. If you stood on Pluto’s Charon-facing side you would see a giant moon hanging almost motionless in the sky, twelve times larger than our Moon appears from Earth, going through phases but never rising or setting.

The four small moons, Styx, Nix, Kerberos and Hydra, are irregular potato-shaped rocks that tumble chaotically because of the gravitational push-and-pull between Pluto and Charon. Discovering them was another surprise, nobody expected such a complex little system.

The hidden ocean nobody saw coming

The biggest scientific bombshell came from studying huge cracks and tectonic features on Pluto’s surface. Many researchers now believe there is a global subsurface ocean of liquid water, possibly 100–200 kilometres deep, kept from freezing by heat from radioactive elements in the rocky core and tidal flexing from Charon. That ocean could easily hold more water than all the oceans on Earth combined. Where there is liquid water, energy, and complex chemistry, scientists always start asking the life question, even if it is just simple microbes.

An atmosphere that freezes and falls

Pluto’s atmosphere is mostly nitrogen with traces of methane and carbon monoxide. It is so thin that spacecraft instruments could barely detect it. When Pluto gets closer to the Sun during its 248-year orbit the surface ices warm up and sublimate, puffing the atmosphere outward. When it swings farther away the entire atmosphere literally freezes and collapses back onto the surface as nitrogen snow. We are watching a world that breathes on a timescale of centuries.

Red snow, methane dunes, and organic chemistry

Large parts of the surface are stained deep red by tholins, complex carbon-rich molecules created when ultraviolet light hits methane in the atmosphere. New Horizons even spotted wind-blown dunes made of frozen methane grains. Pluto has actual weather systems, gentle by Earth standards but real nonetheless.

Why many planetary scientists still call Pluto a planet

The 2006 IAU vote is not the final word. Many researchers, including Alan Stern and much of the New Horizons team, reject the “cleared its neighbourhood” rule as arbitrary and Earth-centric. Exoplanets around other stars almost never fully clear their orbits. They prefer a geophysical definition: if a world is massive enough to be round and has active geology, it is a planet. Under that definition Pluto, Ceres, Europa, Titan, Enceladus, and many others qualify. Recent surveys show only about one-third of planetary scientists accept the IAU decision without reservation. The debate is very much alive in 2025.

Pluto in culture and why we will never let it go

Even after the official demotion Pluto refuses to disappear from our hearts. The New Horizons mission turned it from a blurry dot into a real place with mountains, glaciers, blue skies, and a giant heart. Children today grow up seeing those breathtaking images instead of a blank textbook page. The little spacecraft that travelled billions of kilometres on a perfect trajectory reminded us why we explore in the first place. Pluto became the ultimate symbol of second chances, of underdogs who prove the experts wrong.

In the end Pluto never exploded, never vanished, never stopped being amazing. It was just waiting patiently for us to build better tools and better understanding. The small world that once scared some of us as kids has now become one of the most exciting destinations in the entire solar system, a place with active geology, possible oceans, weather, and a family of weird moons. Size clearly does not matter. Being different is perfectly fine. Sometimes the tiniest worlds carry the biggest stories.

So yes, on paper Pluto is classified as a dwarf planet. But in the data streaming back from New Horizons, in the minds of scientists who study its incredible complexity, and in the memories of everyone who grew up with nine planets, Pluto is still very much one of us. And it always will be.

Keep looking up, friends. The best chapters are usually written about the ones we almost overlooked.

Common Questions

Officially, since 2006 the IAU says no, Pluto is a dwarf planet because it hasn’t cleared its orbit of other Kuiper Belt objects. But many planetary scientists still call it a planet using a geophysical definition (round + active geology = planet). So it depends on who you ask!

Pluto is tiny, only 2,376 km across, less than one-fifth Earth’s diameter. You could fit more than 470 Plutos inside Earth. It’s even smaller than our Moon!

Strong evidence says yes! Huge cracks and young geology suggest a liquid water ocean 100-200 km deep under the ice shell, kept warm by radioactive decay and tidal heating from Charon. It might hold more water than all Earth’s oceans combined.

Charon is so big (half Pluto’s size) that the centre of mass of the system is outside Pluto. So both worlds orbit a point in empty space and are tidally locked, always facing each other. It’s the only true binary planet system we know.

NASA and scientists are already studying an orbiter mission for the 2030s or 2040s. A lander would be even harder, but the dream is alive because Pluto turned out to be way more interesting than anyone expected.

Clyde Tombaugh, a 24-year-old self-taught astronomer, found it in 1930 by comparing photographic plates and spotting a dot that moved. He was looking for the predicted “Planet X” at Lowell Observatory.

References & Further Reading

All links checked and working – November 2025

- NASA New Horizons official mission page

- NASA’s Pluto Fact Sheet (latest 2025 update)

- Johns Hopkins APL – Pluto & Kuiper Belt detailed science summary

- International Astronomical Union (IAU) 2006 Planet Definition & Resolution

- Alan Stern & New Horizons team paper on Pluto’s geology (Nature, 2015)

- Evidence for Pluto’s subsurface ocean (2020 study)

- Clyde Tombaugh biography – Lowell Observatory

- Future Pluto orbiter & lander mission concepts (NASA 2024–2025)