Rogue Planets, Lonely Worlds Drifting Between the Stars

Introduction

Most planets live predictable lives, they orbit a star, they follow a path, and they stay in the “family” of their solar system for billions of years. Rogue planets are the opposite. They are planets that wander through the galaxy without a parent star, basically free floating worlds traveling in deep space…

That idea sounds like science fiction at first, but astronomers have real evidence that these objects exist. Some are likely thrown out of their original planetary systems after violent gravitational chaos. Others might form on their own, like stars do, but they never gain enough mass to ignite and shine. Either way, rogue planets are one of the strangest categories of objects we study today, because they sit right in the messy border between “planet,” “failed star,” and “mystery thing we have not fully named yet.”

Quick note, your message included “first artificial Earth satellite.” That is a totally different topic, the first artificial satellite was Sputnik 1 (launched by the Soviet Union in 1957). Rogue planets are not satellites, they are natural worlds out in space, not built by humans, and not orbiting Earth.

If you are already familiar with normal planets and exoplanets, you will enjoy this more. If not, your own post Exoplanets Guide is a perfect warm up, because rogue planets are often discussed alongside exoplanets, even though many do not orbit a star at all.

What exactly is a rogue planet?

A rogue planet is a planetary mass object that does not orbit a star. Instead of being bound to a single star system, it drifts through interstellar space. You might also see other names like free floating planet, interstellar planet, or orphan planet.

Here is the important detail, “rogue planet” describes an orbit situation, not a “type” of planet like gas giant or rocky planet. In theory a rogue planet could be:

- Rocky, like Earth or Mars, but far colder

- An ice giant, like Uranus or Neptune

- A gas giant, like Jupiter

- A dwarf planet sized object, depending on definitions and formation history

And yes, definitions matter here, because astronomy loves definitions and debates. Some objects found drifting in space are “planetary mass,” but might have formed more like a star in a gas cloud. Astronomers still study them, but people argue about whether to call them true planets. It gets complicated fast, but the science is still fascinating either way.

How do rogue planets happen?

There is no single “one story” for how a planet becomes rogue. Astronomers mainly talk about a few major pathways. Some are dramatic, some are slow, and some are still debated.

1) Ejected from a young planetary system

The most popular idea is gravitational chaos during planet formation. Young star systems are messy places. You get a disk of gas and dust, you get growing protoplanets, you get big objects pulling on each other, and you get a lot of close encounters. In that kind of environment, a planet can be kicked out of the system entirely.

This can happen when:

- A massive planet migrates inward or outward and destabilizes smaller worlds

- Two or more giant planets scatter each other, one gets thrown out

- A close flyby from another star disrupts the system, especially inside star clusters

If you want a mental picture, imagine a crowded dance floor where everyone is moving fast, some people bump, and one person gets pushed right out of the room. That is not perfect physics, but the vibe is similar…

2) Formed alone, like a mini star that never ignited

Another possibility is direct formation in a molecular cloud. Stars form when gas clumps collapse under gravity. If a clump is too small, it might not become a star, but it can still form a warm object with a planetary mass. These objects can look like “planets” by mass, but they did not form in a disk around a star, so some astronomers prefer different labels, like sub brown dwarf or “planetary mass object.”

Either way, from an observational point of view, the sky does not care about our labels. If it has the mass of a planet, and it drifts alone, it still teaches us about atmospheres, chemistry, and formation processes.

3) A planet that survived while its star changed, or got stripped away

This is less common in the usual explanations, but still interesting. In extreme environments like close binary stars, dense clusters, or systems with violent events, planets could be captured, swapped, or stripped from stable orbits. Some may end up on very wide orbits, then later drift away.

In general, the galaxy is not static. Stars move, clusters dissolve, and gravitational “near misses” happen over long time scales.

Are rogue planets common?

This is one of the biggest questions, and the honest answer is, we do not know the exact number yet. We have evidence for them, and we have strong reasons to expect many, but counting them is hard because most are faint and cold.

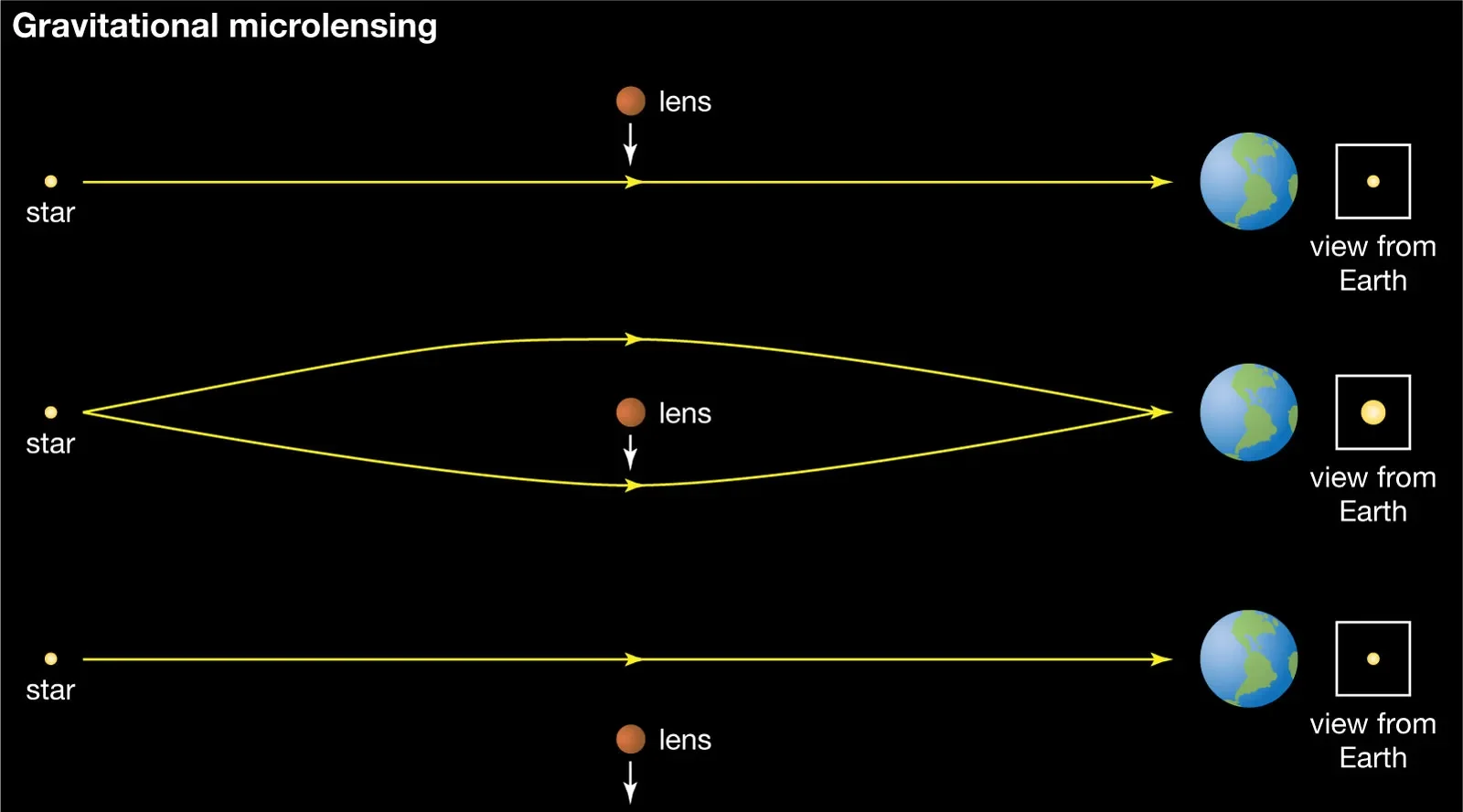

Some research, especially using gravitational microlensing, suggests there could be a huge population of free floating planetary mass objects in the Milky Way, possibly even comparable to the number of stars. But these estimates carry uncertainty, because microlensing events can be tricky to interpret, and it is not always easy to separate a true planet from a small brown dwarf.

So the safe takeaway is: rogue planets likely exist in large numbers, and they might be very common, but the final census is still a work in progress.

Why are rogue planets so difficult to detect?

If a planet orbits a star, you can detect it by watching the star. That is how many exoplanet discoveries happen, via transits and wobbles. But a rogue planet has no bright star next to it, and it usually does not emit much light of its own. That makes the usual methods useless.

Rogue planets are difficult for a few key reasons:

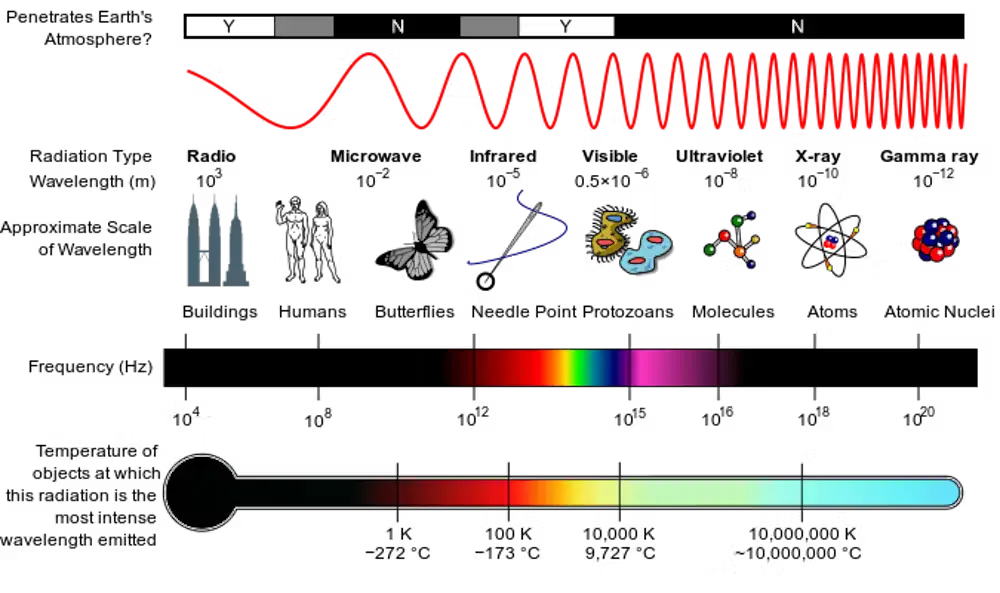

- They are dark and cold, especially older ones, they mostly glow in infrared, and even that can be faint

- They are isolated, no host star to “signal” their presence

- They can be far away, and the galaxy is huge

- They can look like other objects, especially small brown dwarfs, so classification takes careful spectra and models

And there is a sneaky extra problem, even if you detect a free floating object, you still want to know if it truly formed as a planet or formed like a star. That means you need to estimate its age, mass, temperature, and composition, which are not always easy to pin down.

How do astronomers actually find rogue planets?

Even though they are hard to see, scientists have clever methods to detect them. The main ones are infrared imaging and gravitational microlensing, with a few other approaches that help confirm candidates.

1) Infrared surveys, catching their heat glow

Young planets start warmer, and warm objects emit more infrared radiation. That means the easiest rogue planets to detect are often young and relatively nearby, or unusually warm for some reason. Surveys with infrared sensitive telescopes can spot “faint red” objects that do not match normal stars.

Telescopes and missions that have helped with this kind of work include wide field infrared surveys that look for cool brown dwarfs and planetary mass objects. Once a candidate is found, astronomers take spectra to learn about its atmosphere.

2) Gravitational microlensing, using gravity as a detector

Microlensing is one of the coolest tricks in astronomy. When an object passes in front of a more distant star, its gravity bends the starlight and causes a temporary brightening. This does not require the foreground object to emit light. So in theory you can detect a rogue planet even if it is dark, as long as it passes in the right line of sight.

The downside is that microlensing events are rare and one time. You might see it once, then it is gone forever. So scientists rely on monitoring millions of stars to catch these tiny events, and then doing statistics to estimate populations.

3) Direct imaging of wide orbit planets, then asking “is it really bound?”

Sometimes astronomers find very wide orbit planets around stars, and these planets are barely bound. In some cases, follow up observations can show whether the object is actually gravitationally attached or just passing by. It is not the main method for rogue planets, but it is part of the bigger picture of how planets get ejected.

4) Future methods, occultations and deep sky mapping

As sky surveys get more sensitive, there is hope we can detect more rogue planets through subtle events, like a distant star briefly dimming when an object crosses in front of it. This is similar to how small solar system bodies are sometimes found. It is challenging, but the tools are improving fast…

What do rogue planets look like?

People sometimes imagine rogue planets as dead, frozen rocks. Some probably are. But many candidates we can currently observe are young and still warm, and their atmospheres can be active and complex.

Depending on mass and temperature, a rogue planet could have:

- Thick cloud layers, made of silicates or exotic compounds in hotter objects

- Methane and water vapor signatures, common in cooler atmospheres

- Storm systems, like the banded storms of gas giants, but under different heat sources

- High gravity effects, shaping clouds and atmospheric circulation

Some planetary mass objects studied in detail show atmospheric features that look similar to brown dwarfs, which makes sense because the physics overlaps. Temperature and mass decide a lot.

Results so far, examples of real candidates

We do not have a giant list of “confirmed rogues” the way we have confirmed exoplanets, mostly because confirmation is hard. But astronomers have identified multiple strong candidates and free floating planetary mass objects.

One famous example often discussed is PSO J318.5−22, a planetary mass object that appears to wander without a host star, and is young enough to still glow in infrared. There are other candidates identified through infrared surveys and microlensing hints, including extremely cold objects that blur the line between planet and brown dwarf.

The point is not the name list. The point is that multiple independent methods, in different regions of the sky, keep finding objects that fit the “lonely planet mass” idea. That is a strong sign rogue planets are real, and not just theory.

Could a rogue planet have moons?

Yes, it is possible. If a planet gets ejected from its system, it might keep one or more moons, especially if those moons orbit close and the gravitational bond is strong enough. Another possibility is capture, though capture in deep space is harder, because you usually need some way to lose energy.

A rogue planet with a moon is not just a fun idea, it could actually help detection someday. A moon could affect microlensing signals, or create subtle timing features. It could also add tidal heating if the orbit is right, which becomes important when we talk about potential habitability.

Can rogue planets support life?

This is where things get exciting, but we must be careful and realistic. Life as we know it depends on liquid water, energy, and chemistry. A rogue planet has no sunlight, so the surface is likely extremely cold. That sounds like game over…

But there are a few serious scientific ideas that keep the door slightly open:

1) Internal heat, the planet’s own warmth

Planets can generate heat through radioactive decay in their interiors, and through leftover formation heat. Large planets can stay warm inside for a long time. If a rogue planet has a thick insulating atmosphere, it might trap enough heat to keep subsurface oceans from freezing completely.

2) Thick hydrogen atmosphere, a natural blanket

Some studies discuss the idea that a massive rogue planet could retain a thick hydrogen atmosphere. Hydrogen can create a strong greenhouse effect under certain conditions, which might allow surface temperatures to stay higher than you would expect, even without a star. This is not guaranteed, and it depends on many factors, but the concept is scientifically interesting.

3) Tidal heating from moons

If a rogue planet has a moon, tidal flexing could generate heat, similar to how Jupiter’s moon Io is heated, or how Europa may keep a subsurface ocean. This would not make the surface sunny and warm, but it could help maintain pockets of liquid water underground.

So, could life exist on a rogue planet? Maybe in theory, especially underground, but we have no evidence yet. What rogue planets do give us is a wider imagination for where habitable environments could exist, even far from stars.

Why study rogue planets at all?

It is fair to ask this. If rogue planets are cold and dark, why spend telescope time on them? The reason is that rogue planets can answer several big questions at once.

- Planet formation, if many planets are ejected, it tells us early solar systems are more violent than we assumed

- Atmosphere science, without a host star’s glare, we can sometimes study the object’s spectrum more cleanly

- Galactic population, knowing how many rogue planets exist changes our understanding of mass distribution in the Milky Way

- Habitability boundaries, they push the limits of where liquid water and energy could exist

There is also a hidden benefit, rogue planets act like natural laboratories. Some are similar in temperature to giant exoplanets, but you do not have to subtract starlight to study them. That helps refine models we use for distant exoplanets too.

Rogue planets, dark matter, and “hidden stuff” in the galaxy

People sometimes confuse rogue planets with dark matter, because both are “hard to see.” But they are not the same thing. Rogue planets are normal matter, made of atoms, they just do not shine much. Dark matter is something else entirely, it shows up mainly through gravity and does not behave like normal objects.

If you want a clean explanation of what dark matter is and what it is not, your own post Dark Matter Explained, Invisible Universe fits really well as a related read.

Do rogue planets affect other star systems, could they be dangerous?

In movies, rogue planets are sometimes shown crashing into Earth, or causing cosmic disasters. In real life, the galaxy is vast, and space is mostly empty. The chance of a rogue planet wandering close enough to seriously disturb a star system like ours is extremely low.

That said, over billions of years, close stellar flybys do happen. A rogue planet passing near a system could nudge comets or outer objects, but for something truly catastrophic, it would need a very close encounter. Astronomers take these dynamics seriously, but it is not something to worry about day to day.

Rogue planets compared to Pluto, brown dwarfs, and other “borderline” objects

Rogue planets sit in a category where definitions get messy, so comparisons help.

- Pluto is a dwarf planet in our solar system, it orbits the Sun. If you enjoy the classification debate, your post Planet Pluto is a good related read.

- Brown dwarfs are more massive than planets, but not massive enough to sustain hydrogen fusion like stars. Some rogue objects might actually be very low mass brown dwarfs, not planets.

- Free floating planetary mass objects might be “planet mass” but formed like stars, which is why astronomers sometimes avoid calling them planets in strict contexts.

In practice, the universe gives us a spectrum, not neat boxes. That is why this topic stays active, new data keeps changing the story.

What are the biggest challenges and open questions?

Rogue planet science is still young, and there are major unknowns. Here are some of the big ones researchers keep working on:

- How many are there? Is it “a lot” or “ridiculously a lot,” microlensing hints are promising but uncertain

- How do most form? Are they mostly ejected planets, or mostly star like formation objects

- What are their atmospheres like? Clouds, chemistry, wind patterns, these are still being mapped

- Do they commonly keep moons? We have theory, but not enough observational proof

- Could any be habitable? Especially with subsurface oceans or thick atmospheres

Answering these will take better surveys, better infrared sensitivity, and more microlensing statistics. It is slow work, but the progress is real.

Where this research is heading next

The future for rogue planet discovery looks bright, even if the planets themselves are not. Wide sky surveys will watch huge numbers of stars to catch microlensing events more often. Infrared observatories will improve sensitivity to cold, faint objects. And better atmospheric models will help separate “planet like” objects from “brown dwarf like” ones.

There is also a nice connection to other extreme space topics. Rogue planets might pass near stellar remnants, or exist in environments shaped by supernova history. If you enjoy the weird end stages of stars, your post Neutron Stars is worth reading, and for the most famous gravity monsters, What is a Black Hole? links nicely too.

Interesting facts about rogue planets

- Some rogue planet candidates are so young that they still glow strongly in infrared, making them easier to spot.

- Microlensing can detect objects that emit almost no light, which is why it is so important for this topic.

- Rogue planets might outnumber stars in the galaxy, but that claim depends on surveys and interpretation, so it is not “settled” yet.

- A rogue planet with a thick atmosphere could be warmer than you would expect, at least inside or under the surface.

- They help us understand how chaotic planet formation can be, even in systems that look peaceful today.

Final thoughts

Rogue planets are a reminder that the universe is not organized for our comfort. Not every planet gets a warm star and a stable orbit. Some worlds are kicked out early, some form alone, and some drift through the galaxy as silent travelers. Even so, they are not useless leftovers. They are clues.

When astronomers study rogue planets, they are really studying bigger questions, how planetary systems evolve, how common planets truly are, how atmospheres behave in the cold, and where the limits of habitability might sit. It is a topic that starts with a simple idea, a planet without a star, and then expands into a whole new way of thinking about the galaxy…

Common Questions

A rogue planet is a planet sized object drifting through space without orbiting a star.

Mostly through gravity interactions. Young systems can be chaotic, and close encounters with giant planets or nearby stars can eject a planet into interstellar space.

Two main ways, infrared surveys that catch their heat glow, and gravitational microlensing, where their gravity briefly brightens a background star.

We do not know, but some theories suggest subsurface oceans could exist if internal heat and insulation are strong enough. There is no direct evidence of life, it is still speculative.

No. Rogue planets are normal matter, they are just faint. Dark matter is a different mystery that does not behave like ordinary planets or stars.

Not always. Some may form like stars in gas clouds but end up with planet like mass. Astronomers study them either way, but labels can vary depending on formation history.

Reference

- Rogue Planet : Wikipedia

- What are Rogue Planets? : Space.com Guide

- Rogue Planets : Astronomy Cast (Episode 747)