Skylab: America’s First Space Station – A Comprehensive History

Introduction

Skylab, launched by NASA on May 14, 1973, marked the United States’ entry into the era of long-duration space habitation. As the nation’s first orbital space station, it was a repurposed Saturn V third stage transformed into a sophisticated laboratory for scientific research in microgravity. Over its operational period from 1973 to 1974, three crews of astronauts occupied Skylab for a cumulative 171 days, conducting hundreds of experiments that advanced knowledge in solar physics, Earth observation, biomedical effects of spaceflight, and materials science.

Despite suffering severe damage during launch, Skylab’s story is one of resilience and innovation. The first crew performed unprecedented repairs in orbit, saving the mission and demonstrating human ingenuity in space. Skylab’s achievements set records for human space endurance at the time and provided foundational data for future programs, including the International Space Station (ISS).

This article explores Skylab’s origins, design, missions, scientific contributions, daily life aboard, dramatic reentry, and enduring legacy in depth.

Historical Origins and Development

The concept of Skylab traces back to early visions of orbital laboratories. As far back as the 1950s, rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun proposed using spent rocket stages as space stations. By the early 1960s, NASA studied various designs under the Apollo Applications Program (AAP), established in 1965 to extend Apollo hardware beyond lunar missions.

With several Apollo Moon landings canceled due to budget constraints, surplus Saturn V rockets and Apollo spacecraft became available. Initial ideas included a “wet workshop”—refueling and outfitting an S-IVB stage in orbit—but evolved into a “dry workshop”: fully equipping the stage on the ground for safer, more efficient launch.

In 1969, the project was officially named Skylab. McDonnell Douglas converted two S-IVB stages into orbital workshops. The primary Skylab launched in 1973, while a backup is now displayed at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Development involved multiple NASA centers: Marshall Space Flight Center managed overall hardware, Johnson Space Center handled crew systems and operations, and Kennedy Space Center oversaw launch preparations. Industrial designer Raymond Loewy contributed to habitability, emphasizing comfort with features like a wardroom, private sleeping areas, and Earth-viewing windows—novel for spacecraft at the time.

Budget pressures shaped Skylab’s cost-effective approach, repurposing Apollo technology to achieve ambitious goals without new major developments.

Design and Technical Specifications

Skylab was a modular complex weighing approximately 199,750 pounds (90,610 kg) with an attached Apollo Command/Service Module (CSM). Its primary components included:

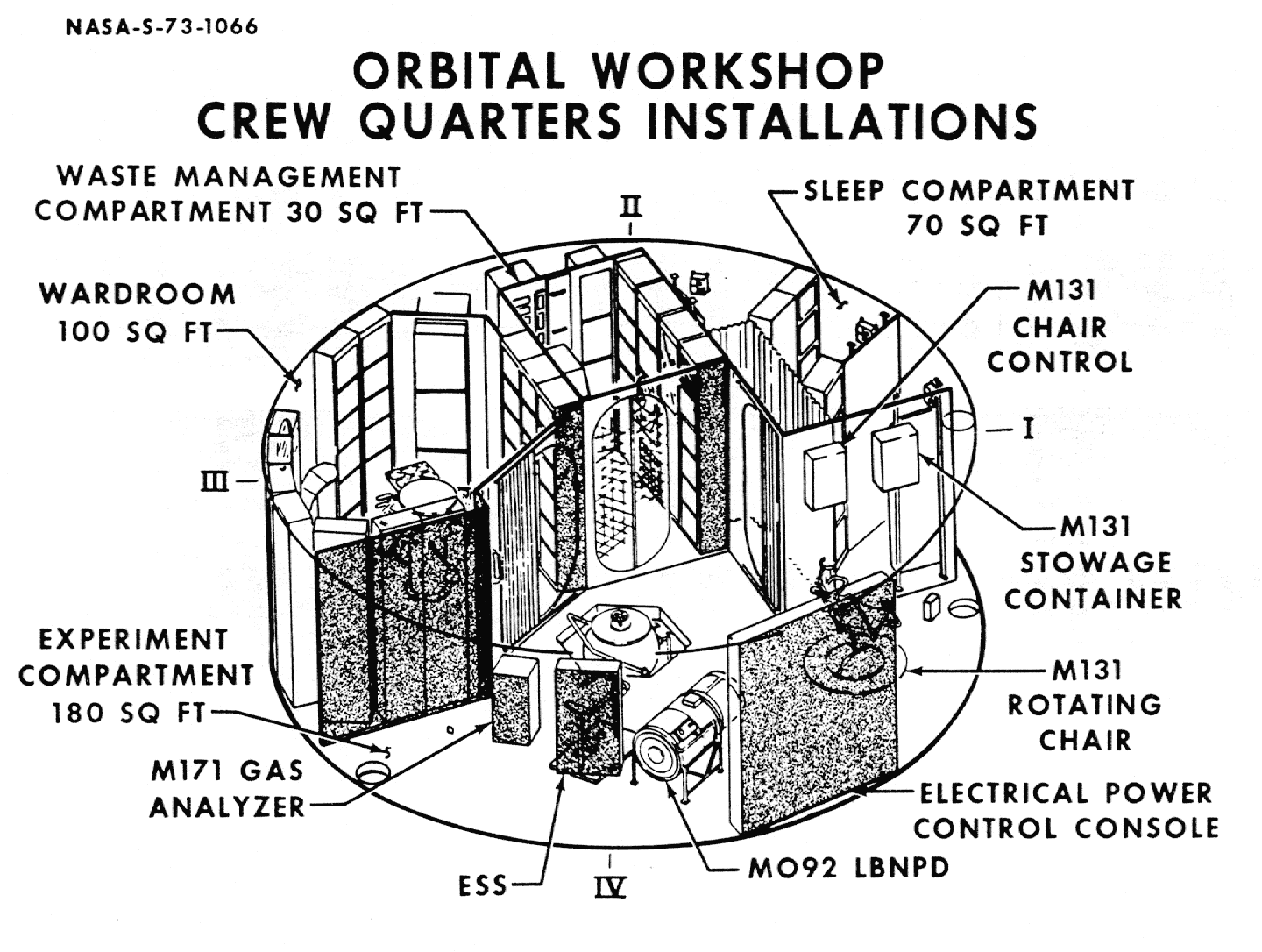

– Orbital Workshop (OWS): The core, converted from the S-IVB hydrogen tank, provided 10,426 cubic feet (295 cubic meters) of habitable volume—comparable to a large house. Divided into two floors: the lower for experiments, sleeping, and waste management; the upper for food storage, hygiene, and additional work areas.

– Airlock Module (AM): 17.6 feet (5.4 meters) long, enabled EVAs and housed attitude control thrusters.

– Multiple Docking Adapter (MDA): Featured two Apollo docking ports (one primary, one for potential rescue) and mounted Earth resources instruments.

– pollo Telescope Mount (ATM): A solar observatory with eight instruments for X-ray, ultraviolet, and visible-light observations, powered by four solar panels.

Power was supplied by two large solar arrays on the OWS (providing up to 12.4 kW) and the ATM’s four panels. Life support recycled water from fuel cells and atmosphere, though limited compared to modern systems. Waste management used a commode with airflow for collection.

Habitability innovations included a galley with 72 food varieties (heated cans, frozen items like ice cream), a dining table, exercise equipment (treadmill, ergometer), a zero-gravity shower (though rarely used due to complexity), and recreational items like books and music.

The station orbited at about 270 miles (435 km) altitude, inclined 50 degrees for diverse Earth views.

Launch and the Initial Crisis

The final Saturn V rocket (SA-513) launched Skylab uncrewed from Kennedy Space Center’s Pad 39A on May 14, 1973.

At 63 seconds after liftoff, aerodynamic forces tore away the micrometeoroid shield (also serving as thermal protection), damaging one main solar array and jamming the other. Debris impacted the station, reducing power to ATM arrays alone and exposing the workshop to intense solar heating—temperatures reached 130°F (54°C) internally, risking equipment and releasing toxins.

The planned Skylab 2 crew launch was delayed 10 days. Engineers devised rapid fixes: a parasol sunshade deployable through a scientific airlock and tools to free the solar wing. These were integrated into the crew’s Apollo CSM.

The Three Crewed Missions

Three crews visited via Apollo CSMs launched on Saturn IB rockets. Total occupation: 171 days.

Skylab 2 (SL-2/SLM-1): Rescue and Repair (May 25 – June 22, 1973; 28 days)

Crew: Commander Charles “Pete” Conrad (Apollo 12 veteran), Science Pilot Joseph P. Kerwin (physician), Pilot Paul J. Weitz.

Upon docking, they deployed the parasol shade, cooling the interior. Multiple EVAs freed the jammed solar array—Conrad and Kerwin used cutters and leverage in a dramatic spacewalk.

Despite repair focus, they conducted solar observations, biomedical tests, and Earth photography, setting a new endurance record.

Skylab 3 (SL-3/SLM-2): Expansion and Observation (July 28 – September 25, 1973; 59 days)

Crew: Commander Alan L. Bean (Apollo 12), Science Pilot Owen K. Garriott (physicist), Pilot Jack R. Lousma.

They installed a twin-pole sail sunshade for better thermal control. Extensive EVAs, student experiments, and observations of solar flares. Doubled the endurance record; included medical studies and Earth resources data.

Skylab 4 (SL-4/SLM-3): Endurance and Comet Kohoutek (November 16, 1973 – February 8, 1974; 84 days)

Crew: Commander Gerald P. Carr, Science Pilot Edward G. Gibson (solar physicist), Pilot William R. Pogue—all rookies.

Observed Comet Kohoutek, conducted four EVAs, and completed thousands of hours of experiments. Workload stress led to a famous “day off” to renegotiate schedules, improving crew-ground relations. Set the final 84-day record.

A backup rescue vehicle was prepared but unused.

Scientific Achievements and Experiments

Skylab hosted nearly 300 experiments, logging 2,000 hours of data.

– Solar Astronomy: ATM instruments captured 127,000 solar images, including coronal mass ejections and flares—impossible from Earth due to atmosphere. Advanced understanding of solar physics.

– Biomedical Research: Studied microgravity effects: bone/muscle loss, fluid shifts, cardiovascular changes. Mandatory exercise mitigated issues; data informed countermeasures still used on ISS.

– Earth Resources: Earth Resources Experiment Package (EREP) and cameras took 46,000 photos, aiding agriculture (crop disease detection), geology, hydrology, and pollution monitoring.

– Materials Science and Other: Grew perfect crystals, produced alloys in microgravity. Student experiments (e.g., cosmic rays, biology) engaged public.

Crews demonstrated in-orbit repairs and human adaptability.

Daily Life and Habitability Aboard Skylab

Skylab’s spacious volume allowed “flying” and somersaults, reducing claustrophobia. Schedules balanced work, exercise (2 hours daily), meals, and rest.

Food: Rehydratable, frozen, and canned items; galley with heaters. Hygiene: Sponge baths mostly; shower cumbersome.

Recreation: Earth views (favorite), music, books. Windows provided psychological benefits.

Challenges: Motion sickness initially, workload fatigue (especially SL-4), minor issues like gyro failures.

Reentry and Demise

Post-SL-4, Skylab was boosted to a higher orbit, hoping for Space Shuttle reactivation. Shuttle delays and heightened solar activity (expanding atmosphere, increasing drag) accelerated decay.

On July 11, 1979, Skylab reentered. Controllers aimed for the Indian Ocean, but breakup occurred lower than predicted. Debris scattered over Western Australia—no injuries.

Media frenzy ensued; Esperance fined NASA $400 for littering (symbolically). Recovered pieces in museums.

Legacy and Influence

Skylab proved long-duration flight viable, with data on human physiology informing ISS countermeasures. Solar and Earth observations remain referenced. Demonstrated EVA repairs and habitability design.

Paved way for Shuttle-Mir cooperation and ISS. Lessons in scheduling, crew autonomy, and microgravity science endure.

Though brief, Skylab exemplified NASA’s adaptability, advancing human space exploration profoundly.

Common Questions

America’s first space station, repurposed from Apollo hardware for long-term orbital research.

Total 171 days across three missions: 28, 59, and 84 days.

Launch damage removed thermal shield and one solar array.

Unprecedented solar observations and human space adaptation studies.

No, debris landed in sparsely populated Australia.