Sputnik 1, The First Artificial Satellite, And The Beep That Started the Space Age

Introduction

On October 4, 1957, a small metal sphere entered orbit around Earth and quietly changed history. It did not carry a camera, it did not map the continents, it did not send high resolution pictures like modern satellites. Instead, it sent a repeating radio signal that sounded like a steady “beep beep” to many listeners. That simple sound became a global announcement that space was no longer just an idea…

This satellite was Sputnik 1, the first artificial Earth satellite. Its success proved something very specific and very difficult, humans could accelerate an object to orbital speed, release it correctly, and keep it circling the planet while transmitting signals that could be detected on the ground. That is the foundation behind almost everything space related that came later, from weather forecasts to navigation systems, from space telescopes to interplanetary probes.

Sputnik is often summarized in one sentence, “first satellite.” But the real story is bigger. It is about why it was launched, what engineers had to solve, how tracking and radio science worked, what the mission showed about the upper atmosphere, and why the world reacted so strongly. This article covers those parts in detail, without drowning you in complicated math.

What does “Sputnik” mean?

The word “Sputnik” comes from Russian and roughly means companion or fellow traveler. It is a surprisingly warm name for such a cold looking object. The idea fits because Sputnik became a companion to Earth, circling the planet again and again, sometimes visible as a moving point of light to people who knew when to look.

The name also helped shape the public image of the launch. Instead of presenting it as a military project, it sounded like a scientific traveler, a “companion” exploring Earth from above. The politics were complicated in the background, but the headline message was clear, humans had reached orbit.

The world before Sputnik 1

To understand why Sputnik mattered, imagine the mid 1950s. Rockets existed, but mostly as experimental vehicles and military designs. Supersonic flight was developing, but space was still treated like a boundary you could not cross. Scientists had written about satellites and orbital mechanics for decades, yet no one had actually done it.

Two big forces were building toward Sputnik:

- Rapid rocket progress, especially large multi stage rockets capable of reaching the speed needed for orbit.

- Cold War competition, where technology was tied to prestige, influence, and security.

There was also the International Geophysical Year (IGY), a worldwide scientific initiative planned for 1957 to 1958. Scientists wanted new data about Earth’s atmosphere, magnetic field, radiation, and weather patterns. Satellites were seen as a powerful new tool for Earth science because they could measure conditions from above the atmosphere, not just from ground stations.

So Sputnik arrived at the intersection of curiosity, capability, and rivalry. That is why it hit so hard when it succeeded.

Why the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 was not launched for just one reason. Several motivations overlapped, and together they created a strong push to be first.

1) Proving orbit was achievable

Reaching space is not enough to orbit. A rocket can go high and still fall back down. Orbital flight requires a huge sideways speed, about 7.8 kilometers per second in low Earth orbit, plus accuracy in timing, direction, and staging. That is why orbit is such a major milestone.

Sputnik 1 proved the Soviet Union could do the full package, build a launch vehicle that could accelerate a payload to orbital velocity, control the ascent well enough to avoid tumbling, and release the satellite at the correct moment. This is a different level of precision than “high altitude rocket.” It meant engineers had mastered guidance, staging, and stability at a scale the world had not seen demonstrated publicly.

In a practical sense, Sputnik also proved that the “space environment” could be survived by hardware. Electronics had to function in vacuum, under rapid temperature changes, and while exposed to radiation conditions higher than on the ground. Sputnik’s success showed that at least a simple spacecraft could stay alive up there.

2) Scientific value, even with a simple payload

Sputnik 1 did not carry complex laboratory equipment, but it still produced useful science. Its radio transmissions allowed researchers to study how signals moved through the ionosphere. The ionosphere can affect radio waves by bending them, delaying them, or causing fading. Tracking how Sputnik’s signal changed during different passes helped improve understanding of radio propagation, which matters for long distance communication.

Another scientific benefit came from Sputnik’s orbit itself. As the satellite traveled through the thin upper atmosphere, it experienced drag. That drag slowly changed its orbital path. By measuring how quickly the orbit decayed, scientists could estimate atmospheric density at altitudes that were difficult to probe at the time. Even today, orbit decay is an important topic, because it affects satellite lifetime and space debris behavior.

So yes, Sputnik was simple, but it was not “just a beep for fun.” The mission gave valuable data and experience at the exact moment scientists were hungry for new ways to observe Earth.

3) National prestige and global influence

Sputnik was a prestige earthquake. Being first in space meant being first in a field that represented the future. Governments, scientists, and ordinary people around the world paid attention because spaceflight looked like the next great frontier, similar to how major inventions reshaped society in earlier eras.

Prestige matters because it influences alliances, confidence, and public perception. If a nation looks technologically ahead, others may treat it differently, or fear being behind. Sputnik created a perception of Soviet leadership in advanced engineering, at least at that moment. That perception itself had real consequences, it pushed more funding into science and technology in other countries, and it made space exploration a serious national priority.

4) Demonstrating rocket capability, indirectly

Even though Sputnik was publicly framed as a scientific satellite, orbital launch capability has obvious implications. If a rocket can place a payload into orbit, it means the rocket can reach extremely high speed and travel long distances. That was not a subtle point for defense planners in 1957.

However, it is important to be precise here. A satellite launch and a military delivery are not identical tasks. They have different trajectories and requirements. Still, Sputnik showed that powerful rockets existed and were operational. That is why Sputnik influenced strategy discussions, not because it was a weapon, but because it was proof of a strong rocket program.

The rocket behind Sputnik, the R-7 family

Sputnik 1 rode into orbit on a rocket based on the Soviet R-7 design family. The key takeaway is capability, the R-7 class had enough lift and enough total impulse to accelerate a payload to orbital speed.

Building a rocket of that scale involved serious engineering challenges. You are not just making a bigger firework. You are building a controlled machine that must survive extreme stresses:

- Structural loads, the vehicle faces intense aerodynamic pressure early in flight and must stay rigid.

- Vibration and resonance, engines and airflow can create vibrations that destroy equipment if not managed.

- Guidance and control, the rocket must steer smoothly, not overcorrect and wobble.

- Stage separation timing, staging must be precise, too early or too late can ruin the trajectory.

The R-7 approach used a core stage with strap on boosters, creating a strong initial thrust. That configuration later became visually iconic in Soviet and Russian launch vehicles, because it worked well and could be developed further. Sputnik’s success helped validate that architecture for the future.

Also, rockets in this era were not like modern “high confidence” systems. Tests were risky, failures happened, and each improvement came from hard lessons. Getting Sputnik into orbit meant the team had reached a level of reliability that could support real missions, not just experimental launches.

Sputnik 1 design, simple on purpose

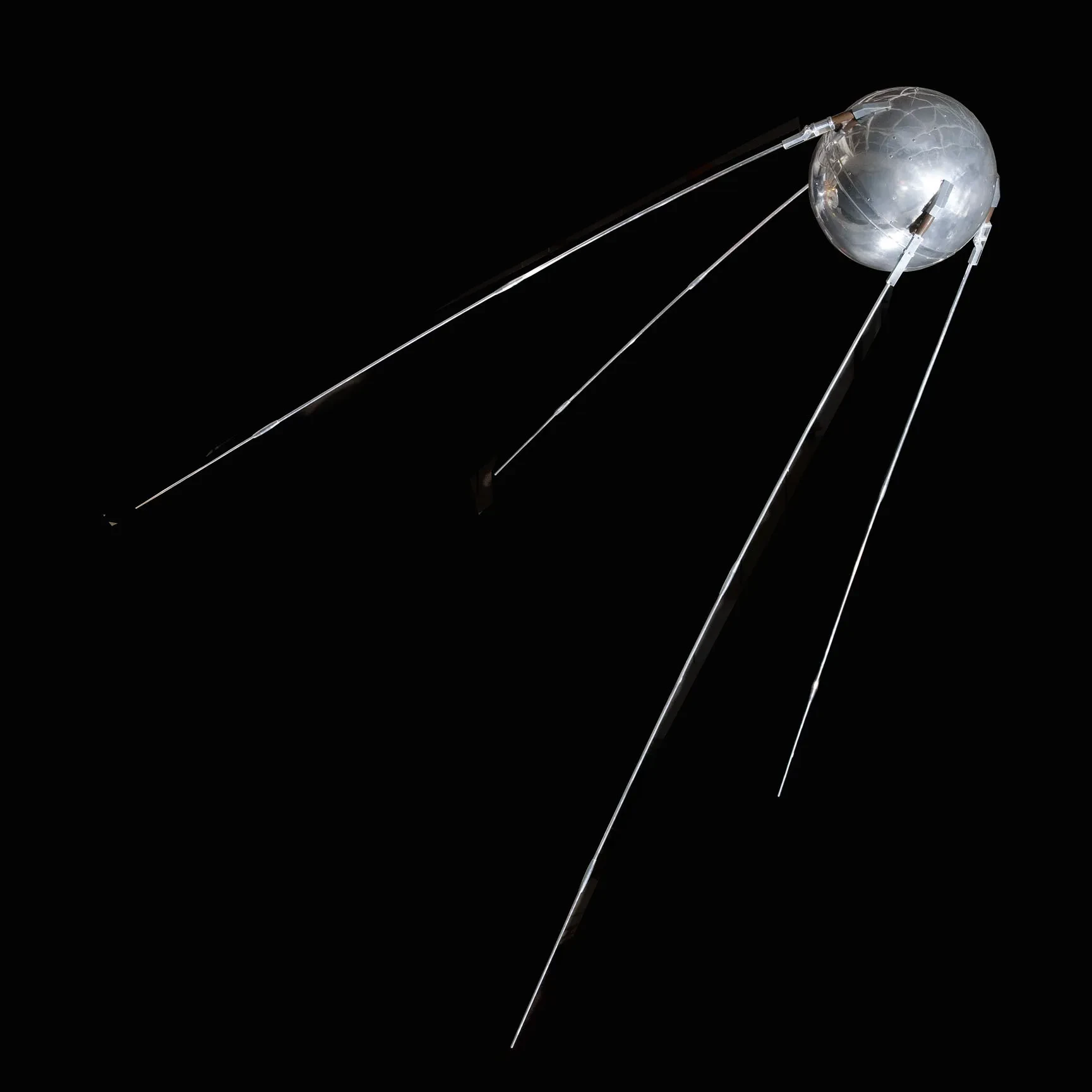

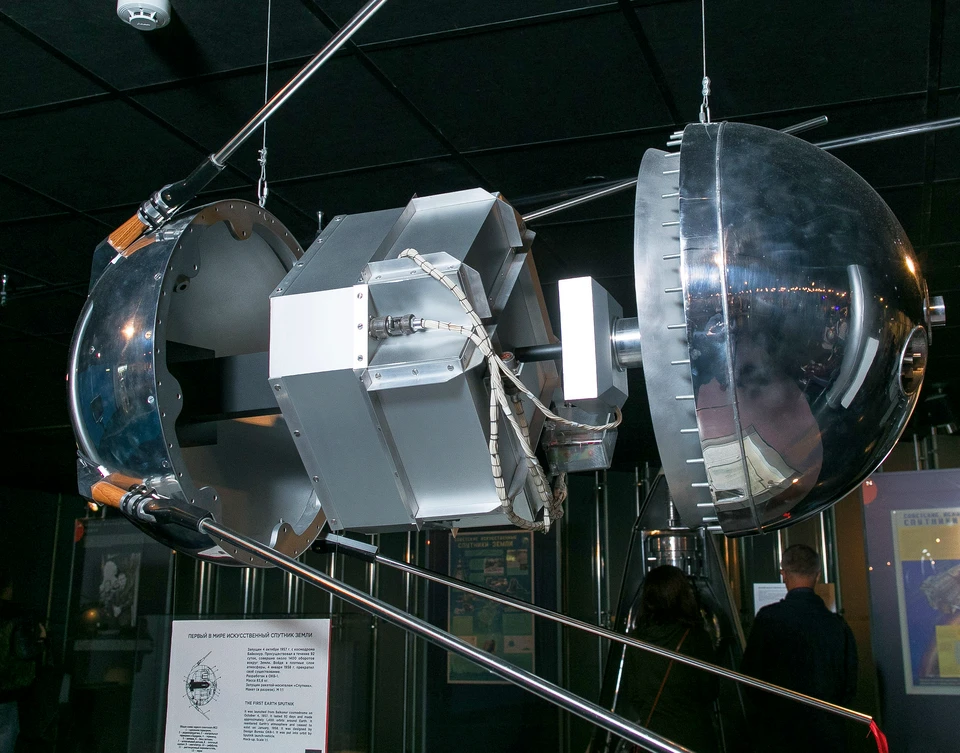

Sputnik 1 was built around a smart idea, if you want the first satellite to succeed, keep the design focused and robust. It was a polished sphere, about 58 centimeters in diameter, with a mass of about 83.6 kilograms. Four long whip antennas extended outward, helping transmit a signal in many directions as the satellite rotated.

Inside were the essentials:

- Two radio transmitters, transmitting on frequencies around 20 MHz and 40 MHz.

- Batteries, powering the transmitters and sensors for a limited time.

- Thermal management, helping keep internal temperatures within operating range.

- Sensors to monitor temperature and pressure, confirming the interior stayed sealed and stable.

That last point is underrated. If pressure inside the sphere dropped unexpectedly, it could mean a leak or structural problem. By monitoring pressure and temperature, engineers could confirm the satellite was intact in orbit. That kind of “health check” thinking is still used in spacecraft today, just with far more sensors.

Key difficulties engineers had to solve

It is easy to say “Sputnik was simple,” but the difficulty was never in making a sphere. The difficulty was making a sphere that could survive launch, function in space, transmit reliably, and be trackable by observers who were still learning how to track satellites.

1) Surviving launch vibration, acceleration, and shock

Rocket launches produce intense vibration, rapid acceleration, and sudden jolts, especially during stage separation. If a component is slightly loose, it can fail. If wiring is not supported properly, it can break. If a solder joint is weak, vibration can crack it. These are small things that become huge at launch loads.

Sputnik’s internal layout had to be mechanically strong. Components needed secure mounts, and the structure needed to resist deformation. Even the antennas had to be designed so they would not snap from vibration or airflow forces during ascent.

This is why early spacecraft often looked “overbuilt.” They were built with simplicity and strength first, because fancy features are useless if the satellite never survives the ride to orbit.

2) Power limits and battery life

Sputnik 1 relied on batteries. That meant a hard time limit. Engineers had to decide how strong the transmitter should be, how often it should transmit, and how to balance battery mass with mission duration.

Think of it like a flashlight in the dark. If you make it extremely bright, it is easier to see, but it runs out faster. If you make it dim, it lasts longer, but fewer people can detect it. Sputnik needed a signal strong enough that stations and even some amateur listeners could pick it up, but not so power hungry that it would die immediately.

The result was a mission that transmitted for about three weeks, long enough to prove success and gather tracking data, while staying within battery limits of the era.

3) Thermal control, heat and cold in orbit

Space is not “cold” in the simple sense. In orbit, you can heat up quickly in sunlight and cool fast in shadow. On Earth, air helps spread heat through convection. In space, heat transfer is mostly by radiation, which behaves differently.

Sputnik’s sphere shape helped with thermal stability because it distributed heat more evenly than many irregular shapes would. Engineers also needed to ensure that electronics and batteries stayed within safe temperature ranges. If batteries got too cold, their output could drop. If electronics overheated, components could fail or behave unpredictably.

This was one of the first real tests of “space thermal engineering,” a field that became critical for later spacecraft and for large observatories like Hubble and James Webb.

4) Radio reliability and signal clarity

The “beep” mattered because it was proof of life. But transmitting from orbit is not the same as transmitting from a tower on Earth. The satellite’s orientation changes, it rotates, it moves rapidly relative to the ground, and it passes through regions of the atmosphere that can disturb radio waves.

Sputnik used a repeating, simple signal so listeners could easily identify it. The dual frequencies also helped because different frequencies can be affected differently by the ionosphere. If one band had interference or unusual fading, the other could still be used to confirm the satellite and study propagation effects.

Also, Sputnik’s signal gave a real world test for ground receivers. Operators learned how to point antennas, reduce noise, and predict passes. That experience helped build the human “software” of early space operations.

5) Tracking, orbit prediction, and global coordination

Once Sputnik was up, the next challenge was knowing where it would be. Today, tracking satellites is routine, with automated systems and public tracking websites. In 1957, satellite tracking was new, and it demanded rapid learning.

Tracking involved multiple methods:

- Radio tracking, listening for the signal during predicted pass windows.

- Optical observation, visually spotting the satellite as a moving point of light at dawn or dusk.

- Orbit calculation, using measurements to refine predictions for the next passes.

Because Sputnik’s orbit covered a wide range of latitudes, it encouraged wider cooperation and multiple observation sites. This helped set the pattern for global tracking networks used in later missions. In a way, Sputnik forced the world to practice “space awareness,” even before that term existed.

Launch day, October 4, 1957

Sputnik 1 launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in what is now Kazakhstan. The rocket lifted off, staged successfully, and released the satellite into orbit. Soon after, radio receivers began detecting its signal, and the news spread globally.

Sputnik’s orbit was elliptical, not perfectly circular. Its lowest altitude was a bit above 200 kilometers, and its highest was near 900 to 950 kilometers. It completed a full orbit in roughly 96 minutes. Its inclination was about 65 degrees, meaning it traveled over large portions of Earth rather than staying close to the equator.

These details matter because they show how technically real the achievement was. This was not a “near space hop.” It was stable orbit, repeated passes, and predictable motion. Many people could see it, and that visibility made it feel personal, like the world had a new moving star.

What Sputnik 1 actually did in orbit

Sputnik 1 did not carry complex cameras or large scientific instruments, but it did something extremely valuable, it created measurable signals and a measurable orbit. From that, scientists extracted data and operational experience.

1) Confirming satellite operation, proving the concept

The first benefit was simple and powerful, proof. The radio pulses confirmed the satellite was alive and transmitting. This confirmed not only that the launch worked, but also that the satellite survived separation and could function in vacuum.

That “survival” aspect is important. Many early rocket tests could reach high altitude, but the payload might fail due to vibration, thermal stress, or electrical issues. Sputnik’s continued transmissions showed engineers had crossed that reliability gap.

Also, the signal made orbit undeniable. It is one thing to announce an achievement, it is another thing to broadcast a signal that anyone with proper equipment can hear. Sputnik made its own evidence.

2) Studying the upper atmosphere through orbital decay

Even at hundreds of kilometers altitude, Earth’s atmosphere is not zero. It is thin, but it produces drag. Drag steals orbital energy slowly, causing the satellite’s path to change over time. By tracking Sputnik’s orbit carefully, scientists could estimate how dense the upper atmosphere was at different heights and during different conditions.

This knowledge was practical. If the upper atmosphere is denser than expected, satellites reenter sooner. If it is thinner, they last longer. Understanding this helped future mission planners choose better orbits for longer lasting satellites.

It also helped research into how the atmosphere responds to solar activity. When the Sun is more active, the upper atmosphere can heat and expand, increasing drag. Sputnik era tracking contributed early data for these relationships, a foundation for what later became space weather studies.

3) Testing radio propagation through the ionosphere

Sputnik’s signals were useful because the ionosphere changes how radio waves behave. Depending on frequency, time of day, and solar conditions, radio signals can be refracted, weakened, or distorted. Sputnik gave scientists a consistent, repeating source moving across the sky, which is perfect for studying these effects.

With two transmitting frequencies, researchers could compare how the ionosphere influenced each band. If one frequency faded more strongly during certain passes, that hinted at how ionospheric layers were interacting with that wavelength. These insights helped refine communication methods, which later became essential for satellites that needed reliable links, not just “beeps.”

In modern terms, Sputnik helped push radio science from theory into orbit tested reality. It was like giving the atmosphere a diagnostic tool.

4) Building tracking networks and operational skills

Sputnik also created a new kind of teamwork. Engineers, scientists, radio operators, and observers all needed to coordinate. Tracking stations had to prepare for pass windows, tune receivers, record signal strength, and share observations.

This operational experience matters because space missions are not only about building the spacecraft. They are also about running it. Even though Sputnik required no commands from the ground, the tracking process trained people in the rhythms of orbital operations. That experience became invaluable when later satellites needed two way communication and active control.

In a sense, Sputnik helped invent the “ground segment” culture of spaceflight. Without that, later missions would have struggled, even if the rockets were good.

How long did Sputnik 1 last?

Sputnik 1’s radio transmissions continued for about three weeks, until its batteries ran out. After that it stayed in orbit silently. It eventually reentered Earth’s atmosphere and burned up in early January 1958, after roughly three months in orbit.

That timeline is a reminder of how quickly early satellites could decay, especially in lower orbits. It also highlights why later spacecraft adopted solar panels, improved thermal systems, and more efficient electronics. Sputnik was a first step, not a final design.

Why the “beep” became famous

Sputnik’s signal was not complicated, and that was the genius. A complex signal would be harder to detect and harder to identify. Sputnik’s repeating pulses were easy to notice, easy to confirm, and easy to describe to the public.

This created a rare situation where ordinary people could feel involved. Amateur radio operators listened for it. Newspapers printed predicted pass times. People went outside to watch the sky. That kind of public participation turned Sputnik into a cultural moment, not just an engineering milestone.

Also, the beep became symbolic. It sounded like a heartbeat from space, steady and calm, but also a little unsettling to some people. A new human made object was circling above everyone, and it was literally making noise. That is unforgettable…

Global reaction, the Sputnik Shock

Sputnik’s impact was technical, political, psychological, and cultural all at once. The world did not react only because it was “cool,” it reacted because it changed assumptions.

1) Public amazement, and a new sense of vulnerability

Many people felt wonder. Space suddenly looked reachable. Science fiction started to feel like tomorrow’s news. Schools talked more about physics. Kids dreamed about rockets. The emotional side was real.

At the same time, some people felt uneasy. If a nation can orbit Earth, it suggests they can build large rockets with high speed capability. Even though a satellite is not the same as a weapon, the concept of long range rocket reach became more concrete in people’s minds. That is why Sputnik created both excitement and fear, depending on who was listening and what they assumed.

The key shift was psychological. Before Sputnik, space felt far away. After Sputnik, it felt close, almost overhead, because it literally was.

2) Acceleration of the space race

Sputnik intensified international competition in space. It forced rapid decisions about funding, organization, and priorities. In the United States, Sputnik is often linked to major changes in education and research investment, plus the eventual creation of NASA in 1958. The goal was not just to “catch up,” but to build a structured civilian space program capable of long term missions.

Competition also accelerated innovation. When countries race, timelines shrink. That pressure can lead to breakthroughs faster than a slow, relaxed approach would. Of course, it also increases risk, but the net effect is that space technology advanced rapidly in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Sputnik was not the only cause, but it was a powerful catalyst, a moment that made spaceflight feel urgent and important.

3) A shift in science culture and engineering education

Sputnik pushed science and engineering into the spotlight. Governments expanded scholarships, funded laboratories, and increased focus on mathematics and physics education. This is one of Sputnik’s long shadows, it helped produce more engineers and scientists over time, and those people later built satellites, computers, communication systems, and medical technology too.

It also changed how big science projects were managed. Space missions require coordination between researchers, manufacturers, test facilities, and operations teams. Sputnik showed that large national projects could create visible results. That lesson influenced later programs, including large telescopes and ambitious robotic missions.

Results and achievements, what Sputnik proved

Sputnik 1 delivered several major “firsts,” and it did so in a clean, verifiable way.

- First artificial satellite successfully placed in Earth orbit.

- First widely observed radio transmission from orbit, proving space to ground communication in a real mission.

- First global satellite tracking event, involving professional stations and amateur observers.

- First public demonstration that orbital launch technology was operational.

Sputnik also proved a deeper point, that space engineering is not magic. It is hard, but it is doable with careful design, testing, and teamwork. That realization opened the gates for later missions with bigger goals.

Benefits to science and everyday life, indirectly

Saying Sputnik “created modern life” is an exaggeration if taken literally, but it is fair to say it helped start a chain reaction. Sputnik made spaceflight credible, which pulled investment and talent into satellite technology.

1) Communication satellites and global connectivity

Once satellites became real, the next question was, what can we do with them? Communication was one of the earliest answers. Satellites can relay signals over long distances, beyond the horizon, without needing thousands of towers. Over time, that concept grew into modern satellite broadcasting, global phone connectivity, and parts of today’s internet infrastructure.

2) Weather forecasting and disaster monitoring

Weather satellites now track storms, cloud systems, ocean temperatures, and climate patterns. This helps forecasting and early warnings for dangerous weather events. Sputnik did not do weather imaging, but it helped establish the reality of orbiting platforms, which later made weather satellites a priority.

3) Navigation, timing, and precision systems

Modern navigation systems depend on satellites and accurate timing signals. Even if you never think about it, satellite timing supports parts of banking networks, telecom networks, and navigation apps. Again, Sputnik was not GPS, but it was the first proof that satellites could exist and be tracked reliably, that is the root of the idea.

4) Earth observation and environmental science

Satellites now monitor deforestation, ice loss, ocean currents, pollution, and land use changes. That helps scientists understand Earth as a system. Sputnik was the first step in this direction, showing Earth could be observed and measured from orbit, even if the earliest measurements were indirect.

Sputnik’s legacy in later missions

Sputnik 1 is like the first step onto a staircase. Each later mission climbed higher, and expanded what “space” could mean.

Space stations took the idea from “objects in orbit” to “humans living and working in orbit.” If you want a strong internal link that continues the timeline, your Skylab article fits perfectly as a next chapter, Skylab, America’s First Space Station.

Deep space probes extended the logic beyond Earth entirely. The gap from Sputnik to Voyager is huge, but the connection is real. Without early orbital success, deep space missions would have been delayed much longer. Your Voyager post is a great example of how far that first beep evolved, Voyager 1 Full Mission Guide.

Space telescopes changed how we observe the universe. By placing telescopes above much of Earth’s atmosphere, we get clearer views, broader wavelength access, and less distortion. That long arc from Sputnik to Hubble and James Webb is one of the most beautiful parts of space history:

Even modern “extreme environment” missions depend on the spacecraft engineering lessons learned over decades. Parker Solar Probe, for example, uses advanced heat shielding and precision navigation, all built on a foundation that began with early pioneers. You can connect readers to your Parker post here, Parker Solar Probe Mission, How NASA Touched the Sun.

Common myths and misunderstandings

Sputnik 1 is famous, and famous things collect myths. Here are the most common ones, cleared up.

- Myth: Sputnik 1 took photos of Earth. Reality, Sputnik 1 had no camera, its key output was radio signals and orbital behavior.

- Myth: The beep was a secret coded message. Reality, it was intentionally simple, easy to detect and verify.

- Myth: Sputnik stayed in orbit for years. Reality, it reentered after a few months, and its transmissions stopped after a few weeks when batteries ran out.

- Myth: Because it was simple, it was easy. Reality, the engineering difficulty was in surviving launch and functioning in space at all, especially in 1957.

Interesting facts about Sputnik 1

- Shape mattered, the sphere helped with structural strength and thermal stability.

- It used multiple antennas, helping signal coverage as the satellite rotated.

- It helped validate satellite tracking methods, radio tracking and optical observation both improved quickly after Sputnik.

- It changed education priorities, increasing focus on science and engineering in many places.

- It made space feel personal, people could listen to it and sometimes see it, which is rare for a technical achievement.

Final thoughts

Sputnik 1 was not the most advanced spacecraft ever built, but it may be one of the most important. It proved orbit was real, it pushed nations to invest heavily in science and engineering, and it created momentum that led to space stations, deep space probes, and powerful telescopes.

If you remember one idea, remember this, Sputnik 1 made space practical. It turned “maybe someday” into “we did it,” and the world never went back..

Common Questions

Its main purpose was to prove a human made object could be placed into orbit and tracked by radio. It also supported basic research on radio propagation and atmospheric drag through orbital tracking.

No. Sputnik 1 did not take photos. Its famous “beep” was its key output, along with the measurable orbit that scientists tracked.

About three weeks, until its batteries were exhausted. The satellite stayed in orbit longer and reentered a few months later.

Because it was the first proof that orbit was achievable. It shifted global assumptions about technology and accelerated investment in science, education, and space programs.

Tracking Sputnik helped estimate upper atmospheric density via orbital decay, and its radio signals helped researchers study how the ionosphere affects transmissions across different frequencies.