The Forgotten Titan: Soviet Union’s Energia Rocket and Its Space Ambitions

Hey folks, if you’re digging into the lesser-known corners of space history, the Energia rocket stands out as a colossal achievement from the Soviet era that often gets lost amid tales of Apollo or the Space Shuttle. Built during the intense final years of the Cold War, it represented the USSR’s push for supremacy in heavy-lift capabilities, a machine that could loft enormous payloads and even a space shuttle into orbit. As someone who’s pored over declassified documents and launch analyses, I find it captivating how this rocket embodied Soviet engineering at its peak, yet flew only twice before vanishing into history. In this deep dive, we’ll explore Energia’s origins, construction, and missions in detail, then shift to in-depth looks at its two payloads, Polyus and Buran. With 2025 marking renewed interest in heavy rockets like Starship, Energia’s story feels timely, showing how past innovations shape today’s space race. Let’s get into it.

Energia: Origins, Builders, Development, and Missions

The Energia rocket, a super-heavy lift launch vehicle, emerged from the Soviet Union’s ambitious space program in the 1970s and 1980s. Its origins trace back to the escalating space race with the United States, particularly after NASA’s Space Shuttle program gained momentum. The Soviets, having suffered setbacks with their N1 lunar rocket which failed spectacularly in four test launches between 1969 and 1972, needed a new heavy-lifter to support large-scale orbital operations, including a reusable space shuttle and potential military applications. The decision to develop Energia came in 1976, as part of the broader Buran program, authorized by the Soviet government to counter what they perceived as a military threat from the US Shuttle, which could theoretically deploy or retrieve satellites for strategic purposes.

Who built it? The primary designer and builder was NPO Energia, a key Soviet aerospace organization based in Moscow, formerly known as OKB-1 under Sergei Korolev but reorganized under Valentin Glushko after Korolev’s death in 1966. Glushko, a renowned rocket engine designer, led the project, bringing his expertise in propulsion systems. NPO Energia coordinated with numerous subcontractors across the USSR, including Ukrainian facilities like Yuzhmash for booster production and Kazakh sites for assembly. Thousands of engineers, technicians, and workers were involved, drawing on expertise from previous programs like the Proton and Soyuz rockets. The modular design was a collaborative effort, with contributions from institutes like TsNIIMash for structural testing and the Khrunichev plant for manufacturing key components.

The origin story is rooted in Cold War paranoia and technological rivalry. After the N1’s cancellation in 1974, Glushko advocated for a new approach using liquid propellants instead of the N1’s problematic kerosene-based system. Energia was conceived as a versatile launcher, capable of configurations from 20 to 100 tons to low Earth orbit, depending on the number of boosters. This flexibility set it apart from fixed-design rockets like Saturn V. The name “Energia” itself reflects its power, derived from the Russian word for energy, symbolizing the immense thrust it generated.

How long did it take to develop? The project officially started in 1976 with conceptual designs, but full-scale development ramped up in the early 1980s. Technical proposals were completed by 1978, and a full-scale mockup was built by 1979 for wind tunnel and integration tests. Engine development for the RD-170 and RD-0120 began earlier, with the RD-170’s design dating back to 1976. Ground testing of components stretched into the mid-1980s, including static fires at Baikonur. Challenges included supply chain issues across the vast USSR, material shortages, and integrating advanced avionics with limited computing power. By 1985, assembly of the first flight article began, and the rocket was ready for its debut launch in 1987. Overall, it took about 11 years from inception to first flight, a remarkable pace considering the scale, though rushed compared to the typical five-year Soviet project cycles for smaller vehicles.

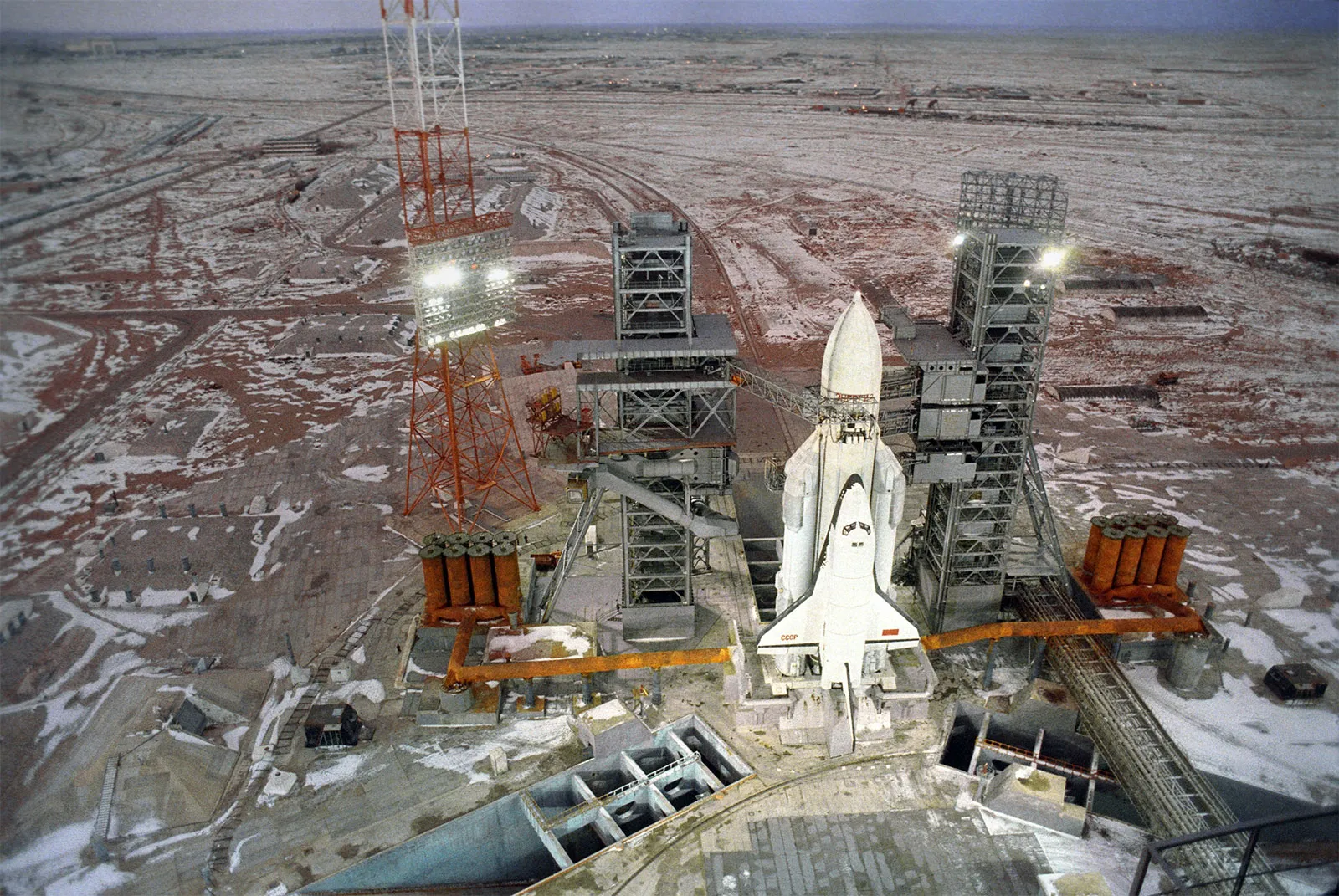

During development, engineers faced numerous hurdles. The RD-170 engine, the world’s most powerful liquid-fueled rocket engine at the time with 1.7 million pounds of thrust, required innovative chamber designs to handle kerosene and liquid oxygen without instability. The central core’s RD-0120, using liquid hydrogen, was a first for the Soviets, demanding new cryogenic handling techniques. Structural integrity was tested against vibrations, a lesson from N1 disasters. The boosters were designed for potential reuse, with parachutes and soft-landing systems, but this feature was never fully realized due to costs. Baikonur Cosmodrome’s Site 250 was modified extensively, including new pads and assembly buildings, adding to the timeline. Political pressures from leaders like Leonid Brezhnev and later Mikhail Gorbachev accelerated work, but economic strains in the 1980s caused delays in funding.

Energia’s specifications were impressive: 58.7 meters tall, 17.6 meters wide at the base with four boosters, gross mass of 2,400 tons. It produced over 7.5 million pounds of liftoff thrust. The core stage burned for 480 seconds, boosters for 140. Payload fairings could accommodate massive cargoes up to 18 meters long. Compared to contemporaries, it matched Saturn V’s capacity but offered modularity, like using two boosters for lighter loads.

How many missions and what were they? Energia flew only twice, both from Baikonur’s Pad 250. The first mission on May 15, 1987, carried the Polyus spacecraft, an experimental military platform intended for orbital weapons testing. The rocket performed flawlessly, but Polyus failed to achieve orbit due to a guidance error, re-entering over the Pacific. This launch validated Energia’s design, though the payload loss was a setback. The second mission, on November 15, 1988, launched the Buran orbiter, the Soviet space shuttle, on an unmanned test flight. Buran orbited Earth twice, conducted experiments, and landed automatically at Baikonur, marking a success. No further missions occurred; the program was canceled in 1993 amid the USSR’s collapse, with several rockets left unfinished. Potential future uses included launching Mir-2 modules or interplanetary probes, but economic turmoil ended those plans. Energia’s brief history highlights the era’s ambitions and fragilities, with its technology influencing modern Russian launchers like Angara.

To expand on the missions’ context, the 1987 launch was shrouded in secrecy, with Polyus disguised as a civilian satellite. Energia’s performance data showed precise staging and thrust control, boosting confidence for the Buran flight. The 1988 mission demonstrated the system’s full capability, with Buran separating cleanly and the core disposing safely. Post-flight analysis revealed minor issues like booster separation dynamics, but overall success. The program’s end left a legacy of untapped potential; had it continued, Energia might have supported a Soviet space station rivaling the ISS. In total, these two flights showcased what could have been a cornerstone of Soviet space dominance, but history took a different turn.

Polyus Mission: A Deep Dive into the Soviet Orbital Weapon Prototype

The Polyus mission, launched on May 15, 1987, represents one of the most intriguing and secretive episodes in Soviet space history. As the payload for Energia’s inaugural flight, Polyus (also known as Skif-DM or 17F19DM) was a massive prototype spacecraft designed primarily as an orbital weapons platform, part of the USSR’s response to the US Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), dubbed “Star Wars” by President Reagan in 1983. The SDI aimed to develop ground- and space-based systems to protect against nuclear missiles, prompting the Soviets to accelerate their own anti-satellite and missile defense technologies. Polyus was envisioned as a laser-armed satellite capable of destroying enemy spacecraft or incoming warheads from orbit, embodying the Cold War’s escalation into space militarization.

Development of Polyus began in earnest around 1985, under the leadership of the Chelomey Design Bureau (OKB-52), later part of NPO Mashinostroyeniya. The project was rushed to coincide with Energia’s readiness, as Buran was delayed, leaving the rocket without a payload for its test launch. Normally, Soviet space projects followed five-year development cycles, but Polyus was compressed into about two years, leading to compromises. Engineers repurposed existing hardware from the TKS spacecraft and Salyut space stations, including a functional module for attitude control and docking capabilities. The spacecraft measured 37 meters long and 4.1 meters in diameter, weighing approximately 80 tons, making it one of the heaviest payloads ever attempted.

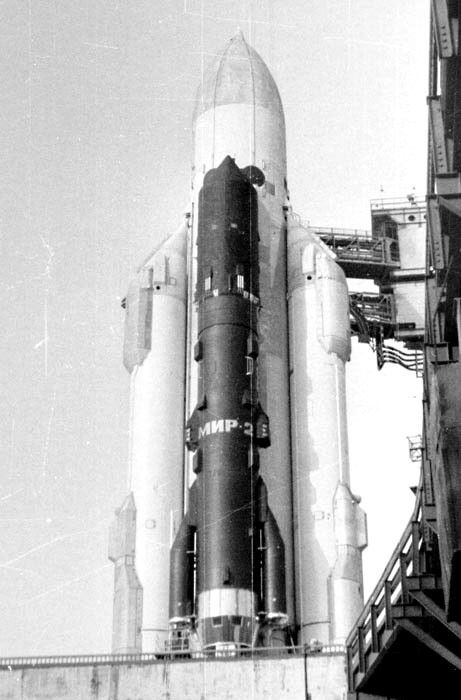

The “how” of Polyus involved innovative yet hasty engineering. Its structure was cylindrical, divided into sections: a forward laser compartment, a central service module with solar panels and thrusters, and a rear engine block. The primary weapon was a 1-megawatt carbon dioxide laser, fueled by xenon and powered by turbo-generators. Ground tests at facilities like Terra-3 demonstrated beam focusing, but orbital challenges like vacuum distortion and targeting accuracy remained unresolved. Polyus also carried a cannon for launching decoy targets, radar systems for detection, and even a resupply tug for orbital maneuvering. For safety, the laser was defueled during launch, and dummy weights replaced live components. The spacecraft was painted black to reduce visibility, and names like “Polyus” and “Mir-2” were added to mask its military purpose as a potential successor to the Mir station.

When did it happen? Assembly occurred at the Khrunichev plant in Moscow from late 1985 to early 1987, with integration at Baikonur Cosmodrome. The launch date, May 15, 1987, was symbolic, aligning with Soviet May Day celebrations and showcasing technological prowess amid arms talks with the US. Where? Baikonur’s Site 250, a dedicated pad for Energia, in the Kazakh SSR. The site featured massive assembly halls and fuel storage for the rocket’s cryogenic propellants.

Why Polyus? The mission’s core objective was to test orbital laser weaponry against SDI threats. Soviets feared US satellites could blind their reconnaissance or guide missiles, so Polyus aimed to demonstrate anti-satellite capabilities. It carried experiments for beam propagation, target acquisition, and decoy deployment. Politically, Gorbachev pushed for it despite his disarmament rhetoric, viewing it as leverage in negotiations. The rush stemmed from Energia’s timeline; without Polyus, the rocket’s debut might have been postponed.

The launch sequence was flawless for Energia, achieving nominal ascent and stage separation. However, Polyus was mounted upside-down on the rocket for aerodynamic stability during atmospheric flight. After separation at about 140 km altitude, it needed to rotate 180 degrees using its attitude thrusters before igniting its orbital insertion engines. A software glitch or sensor failure caused it to spin incorrectly, firing the engines in the wrong direction and propelling it back toward Earth. The result? Polyus re-entered the atmosphere minutes later, disintegrating over the Pacific Ocean south of Hawaii. No debris was recovered, and the mission was deemed a failure, though Energia itself succeeded.

Deeper analysis reveals the failure’s causes: inadequate testing due to the compressed schedule, with simulations missing edge cases in attitude control. Declassified documents show the rotation command was delayed by a timer error, leading to over-rotation. The mission’s secrecy limited international scrutiny, but internal reviews criticized the haste. Results included valuable data on heavy payload deployment and laser tech feasibility, feeding into later Russian programs like the Peresvet ground-based laser. Polyus highlighted arms race perils; if successful, it might have violated emerging space treaties and provoked escalation. In 2025 context, it echoes current concerns over space weapons, with nations like Russia testing ASAT missiles. The project’s legacy is a cautionary tale of ambition outpacing caution, with Polyus symbolizing the unrealized Soviet space empire.

Buran Mission: The Soviet Shuttle’s Sole Flight and Program Legacy

The Buran mission, culminating in its lone flight on November 15, 1988, stands as a pinnacle of Soviet aerospace achievement and a poignant symbol of unfulfilled potential. Buran, meaning “snowstorm” in Russian, was the USSR’s reusable space shuttle, developed as a direct counterpart to NASA’s Space Transportation System. The program began in 1974, authorized by the Central Committee in February 1976, amid fears that the US Shuttle could serve military roles like satellite capture or orbital bombing. Unlike NASA, the Soviets integrated Buran with Energia, offloading main engines to the rocket for greater payload capacity.

How was Buran built? Under Gleb Lozino-Lozinsky at NPO Energia, development spanned over a decade, involving 1,200 organizations and 2.5 million people. The orbiter’s design mirrored the US Shuttle externally for aerodynamic reasons, but internals differed: no main engines, auxiliary jets for powered landings, and advanced automation for unmanned flights. Construction started in 1980 at the Tushino Machine-Building Plant near Moscow, with the first flight article, OK-1.01, completed in 1986. Heat shielding used 38,000 silica tiles, similar to NASA’s but with Soviet materials. Testing included 25 atmospheric flights atop the An-225 Mriya, the world’s largest aircraft, built specifically for Buran transport.

The program’s origin lay in Cold War strategy. Initial concepts dated to the 1950s with spiral designs, but Buran coalesced after US Shuttle approval in 1972. Soviets spied on NASA via open sources and intelligence, adapting but innovating, like Buran’s auto-landing system using Soviet computers. Development took 12 years to first flight, delayed by economic issues and technical hurdles like tile adhesion in extreme colds.

When and where? The mission launched from Baikonur’s Site 110 on November 15, 1988, after weather delays. Buran orbited at 250 km, completing two laps in 3 hours 25 minutes, then landed at Yubileyny Airfield despite gusty winds.

Why Buran? To achieve reusable access for satellite ops, space station support, and military reconnaissance. The unmanned test proved autonomy, carrying instruments for materials science and Earth observation. The flight was a success: clean separation, orbital maneuvers, and precise landing 3 meters off centerline.

Results? Validated design, but the program ended in 1993 after USSR dissolution, with orbiters mothballed. One was destroyed in a 2002 hangar collapse. Legacy influences modern vehicles like Dream Chaser. In depth, Buran had superior automation, could fly 30 days manned, and carried 30 tons. Challenges included funding cuts post-1988, shifting priorities to Mir. If continued, it might have ferried crews to ISS precursors.

Common Questions

A Soviet super-heavy lift launcher from the 1980s, capable of 100 tons to orbit, modular design with boosters.

NPO Energia under Valentin Glushko, with contributions from various USSR facilities.

Response to US Space Shuttle, after N1 failure, started in 1976.

About 11 years, from 1976 to first launch in 1987.

Two: Polyus in 1987 and Buran in 1988.

A 1987 launch of a military orbital laser platform that failed to reach orbit.

Attitude control error caused wrong engine firing direction.

Unmanned 1988 test flight, two orbits, successful auto-landing.

Economic issues after USSR collapse in 1991.

Its RD-170 engine variants power current launchers like Atlas V.

References & Further Reading

- Wikipedia: Energia (rocket)

- RussianSpaceWeb: Energia

- Britannica: Energia

- Wikipedia: Polyus (spacecraft)

- The Space Review: Barbarian in space

- Smithsonian Magazine: Soviet Star Wars

- Space.com: Buran — The Soviet space shuttle

- Smithsonian Air & Space: The Soviet Buran Shuttle

- National Interest: The Untold Story of Russia’s Buran Space Shuttle

- RussianSpaceWeb: History of Energia-Buran facilities